Well it wasn't originally, but it is now.That's wild!

What have you learned today?

- Thread starter hanselthecaretaker

- Start date

The clearest memories of that helmet that I have both involve Hogan’s Heroes. Mainly that Hogan often messes around with one Klink has on his desk (moving it, playing with the spike and on one memorable occasion tricking Klink into sitting on it) and as the still image over the end credits, with Hogan’s Army Airforce officer’s cap draped over it by the spike.Something I learned today.

The famous German Spiked Helmet, the Pickelhaube aka Pickaxe Helmet, was only in service in the German Army for less then a century and was phased out in WW1. It turns out the spike made it much easier to be spotted in the Trenches, and at first they just made the spike detachable and not to be worn on the front line. However, the Helmet itself was apparently not terribly useful at protect the old noggin from shrapnel and such and was relegated to ceremonial wear before being discontinued entirely. It was replaced with a steel helmet(the Stahlhelm or literally "Steel Helmet"), the one the German Army wore in WW2, which was replaced in the 1990's by the Gefechtshelm( Literally "Combat Helmet"). God Bless those Germans, just calling thing the literal thing it is instead of making up flashy names.

Also the US Marines breifly had their own version from the 1890s to 1904.

Seems the brain injury from Memento is far more debilitating to live under in real life than in the fiction. 30 seconds for each memory reset is bloody awful: you ain't getting any tattoos in that time, hell you probably can't even write a useful post-it note neither. There's just not enough time to even properly consider your own condition and experience normal emotions from such information. Is impossible to imagine what it must be like.

Yes. I’m not sure what math he’s using to jump to such a conclusion. If getting screened early can mean the difference between having to shit in a bag or not for the rest of your life let alone dying from the cancer that decided it, then it would seem to be worthwhile.I’ve never heard any doctor claim the mere action of having a fibre optic camera shoved up your gravy trumpet extends your life. Just that it can help at certain points of life in detecting bowel cancer. Among many other preventative measures; but I’m guessing early cancer detection is what actually adds years to your life.

Last edited:

As recounted here above,

During WW2, a German Navy task force was accidently bombed by a Luftwaffe bomber squadron because neither force was told the other would be the in the area and due to a series of unfortunate events, Search and Rescue Operations ended up happening in conjunction with trying to depth charge submarines that didn't exist. A ship and over 500 Kriegsmarine Sailors were lost but nobody was held accountable because of course nobody was.

Not to be outdone, British Admiral Anson led a circumnavigation of the globe with a force of 1854 sailors and marines and 8 ships. Only one ship and 188 men completed the journey(though 500 survived in total once you count ships that turned back to England earlier in the voyage). Despite the incredibly high loss rate, the Admiral was offered a promotion. Almost everyone that died did so due to scurvy or starvation. No failing like failing upwards.

I feel like there's a joke here.

Kreigsmarine: Ve bombed our own task force, lost a warship and 500 men and held no one accountable.

Royal Navy: Hold my rum, you bloody amateurs. We'll show you how a true cock-up is done.

Last edited:

Consider who's making the argument there. No worth to it.Yes. I’m not sure what math he’s using to jump to such a conclusion. It getting screened early can mean the difference between having to shit in a bag or not for the rest of your life let alone dying from the cancer that decided it, then it would seem to be worthwhile.

As for me, I did the "poop in a bucket and mail it out" test. Just got the results today: Negative.

I hate to be that guy, but lunatic you linked in Wikipedia died in 1762.

As recounted here above,

During WW2, a German Navy task force was accidently bombed by a Luftwaffe bomber squadron because neither force was told the other would be the in the area and due to a series of unfortunate events, Search and Rescue Operations ended up happening in conjunction with trying to depth charge submarines that didn't exist. A ship and over 500 Kriegsmarine Sailors were lost but nobody was held accountable because of course nobody was.

Not to be outdone, British Admiral Anson led a circumnavigation of the globe with a force of 1854 sailors and marines and 8 ships. Only one ship and 188 men completed the journey(though 500 survived in total once you count ships that turned back to England earlier in the voyage). Despite the incredibly high loss rate, the Admiral was offered a promotion. Almost everyone that died did so due to scurvy or starvation. No failing like failing upwards.

I feel like there's a joke here.

Kreigsmarine: Ve bombed our own task force, lost a warship and 500 men and held no one accountable.

Royal Navy: Hold my rum, you bloody amateurs. We'll show you how a true cock-up is done.

He did. But the scale of his folly transcends the fact he did it first. And the fact the joke isn't as funny when it's "and centuries later some Germans blew themselves up on accident", even if it is a perfect real life example of the "cock up cascade"I hate to be that guy, but lunatic you linked in Wikipedia died in 1762.

Well it certainly explains why nothing happened to him. Also I can imagine him watching that Kreigsmarine stuff up and saying “Amaturs” in the most British, toffy nosed accent ever.He did. But the scale of his folly transcends the fact he did it first. And the fact the joke isn't as funny when it's "and centuries later some Germans blew themselves up on accident", even if it is a perfect real life example of the "cock up cascade"

Eh, back then everyone just accepted that sailors died of disease. The solution was often to pack the ship with as many people as possible so that there'd be spares, and the close proximity made disease spread faster. Though, not the big one, scurvy killed more people than all other causes combined, (in wartime you could lose 10 times as many to scurvy as to direct enemy action). There was massive institutional inertia preventing anything getting done about it.

Sure, you can blame the admiral, but everyone else who was aware of the voyage would have known in advance that most people involved were going to die, generally slowly and horribly. Scurvy is a bad way to go.

Loads of weird quack science was proposed as cured. One nasty thing they tried was to work the sick harder, because one symptom of scurvy is a lack of energy, some people decided laziness was the cause.

There's talk about Cook's voyage to Australia as proving that citrus fruit could stop scurvy, but that, AFAIK, is only kinda true. He tried something like 6 methods for combating scurvy, the crew didn't get it, he was happy (they were too, I presume), but didn't know which method it was. It was some years later before they worked it out, but it was too expensive so they just dithered and let people die. Later they tried it for a bit, prevented scurvy, someone decided they problem was fixed and so it was too expensive to continue providing citrus fruits so they stopped and scurvy, to everyone's surprise, came back.

As an aside, Pringle, head of the British medical establishment, being in his ivory tower, refused to accept the proof that they could prevent scurvy, despite lots of other, less important people having understood it by then. Until he died and was replaced, no progress could be made. He was in power during the American War of Independance, where the British fleet suffered defeats at the hands of the French, which was a big part of ultimate rebel success. If Pringle had instituted measures to combat scurvy, the Royal Navy would have been more efficient and the rebellion might have been defeated.

TL;DR, there was a entire institution of getting things horrifically wrong and refusing to change in the Royal Navy, and it seems every other at that time.

Sure, you can blame the admiral, but everyone else who was aware of the voyage would have known in advance that most people involved were going to die, generally slowly and horribly. Scurvy is a bad way to go.

Loads of weird quack science was proposed as cured. One nasty thing they tried was to work the sick harder, because one symptom of scurvy is a lack of energy, some people decided laziness was the cause.

There's talk about Cook's voyage to Australia as proving that citrus fruit could stop scurvy, but that, AFAIK, is only kinda true. He tried something like 6 methods for combating scurvy, the crew didn't get it, he was happy (they were too, I presume), but didn't know which method it was. It was some years later before they worked it out, but it was too expensive so they just dithered and let people die. Later they tried it for a bit, prevented scurvy, someone decided they problem was fixed and so it was too expensive to continue providing citrus fruits so they stopped and scurvy, to everyone's surprise, came back.

As an aside, Pringle, head of the British medical establishment, being in his ivory tower, refused to accept the proof that they could prevent scurvy, despite lots of other, less important people having understood it by then. Until he died and was replaced, no progress could be made. He was in power during the American War of Independance, where the British fleet suffered defeats at the hands of the French, which was a big part of ultimate rebel success. If Pringle had instituted measures to combat scurvy, the Royal Navy would have been more efficient and the rebellion might have been defeated.

TL;DR, there was a entire institution of getting things horrifically wrong and refusing to change in the Royal Navy, and it seems every other at that time.

Behold! Bask in the synthetic majesty of ...DISHBRAIN!

(Absolutely ripe material for the next sci-fi horror dystopian novel/film/videogame story )

)

www.sciencealert.com

www.sciencealert.com

Wait, hold up...when can we party with Dishbrain??

(Absolutely ripe material for the next sci-fi horror dystopian novel/film/videogame story

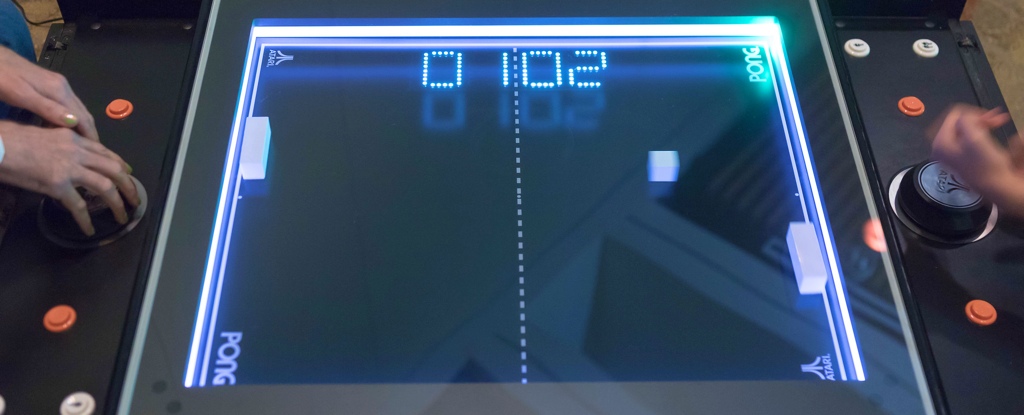

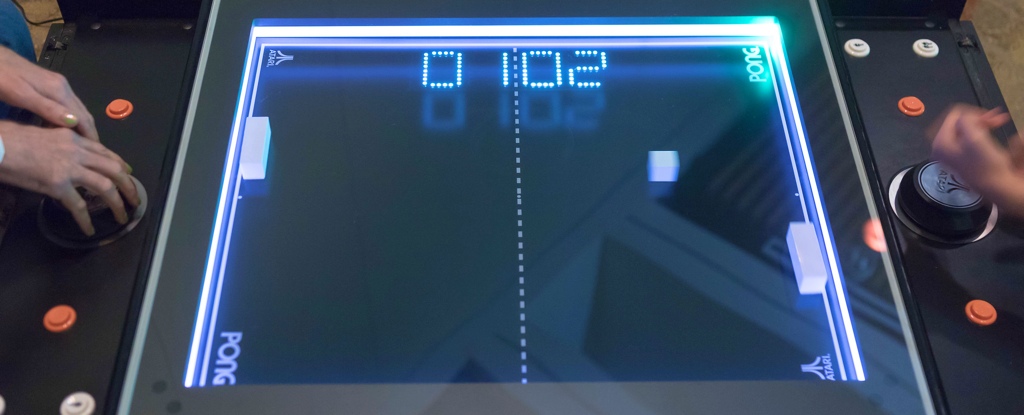

WATCH: A Dish of Brain Cells Figured Out How to Play Pong in 5 Minutes

How many brain cells does it take to play a video game? No, really.

~insane in the dishbrain~How many brain cells does it take to play a video game?

No, really. That's not a joke, and there isn't a punchline. Instead, there's a real actual answer, thanks to a neural network system called DishBrain.

If that game is Pong, the number of brain cells is around 800,000.

While their slow-moving, one-sided strategy for digital table tennis won't see them win any e-sports championships in the near future, it does reflect the potential in fusing living tissues with silicon technology.

This is the first synthetic biological intelligence experiment that shows neurons can adjust their activity to perform a specific task – and, when provided with feedback, can learn to perform that task better. It's pretty amazing stuff, with potential applications in computing, as well as studying all sorts of brain stuff, from how drugs and medication impact brain activity to how intelligence develops in the first place.

"We have shown we can interact with living biological neurons in such a way that compels them to modify their activity, leading to something that resembles intelligence," says neuroscientist Brett Kagan of biotech startup Cortical Labs in Australia.

DishBrain is a heady mix of neurons extracted from embryonic mice and human neurons grown from stem cells. These cells were grown on arrays of microelectrodes that could be activated to stimulate the neurons, thus providing sensory input.

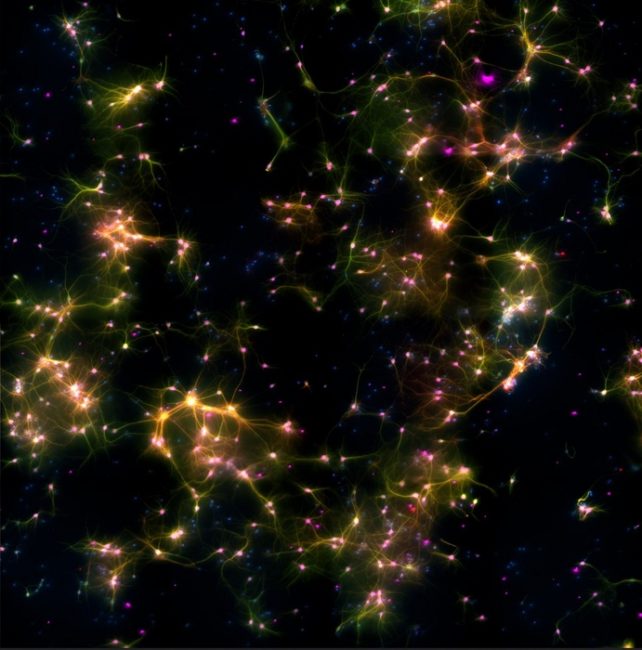

Under the microscope, tagged with fluorescent markers, the neurons, axons and dendrites glow purple, red and green. (Cortical Labs)

For a game of Pong, microelectrodes on either side of the dish indicated whether the ball was to the left or right of the paddle, while the frequency of signals relayed the ball's distance.

With just this set-up, DishBrain is capable of moving the paddle to meet the ball, but performs pretty poorly overall. In order to play the game well, the neurons need feedback.

The team developed a software to deliver critique via electrodes whenever DishBrain missed the ball. This allowed the system to improve at playing Pong, with learning observed by the researchers in as little as five minutes.

"The beautiful and pioneering aspect of this work rests on equipping the neurons with sensations – the feedback – and crucially the ability to act on their world," says theoretical neuroscientist Karl Friston of University College London in the UK.

"Remarkably, the cultures learned how to make their world more predictable by acting upon it. This is remarkable because you cannot teach this kind of self-organization; simply because – unlike a pet – these mini brains have no sense of reward and punishment."

A few years ago, Friston developed a theory called the free energy principle, which proposes all biological systems behave in ways that reduce the gap between what is expected and what is experienced – in other words, to make the world more predictable.

By adjusting its actions to make the world more predictable, Friston says, DishBrain is simply doing what biology does best.

"We chose Pong due to its simplicity and familiarity, but, also, it was one of the first games used in machine learning, so we wanted to recognize that," Kagan says.

"An unpredictable stimulus was applied to the cells, and the system as a whole would reorganize its activity to better play the game and to minimize having a random response. You can also think that just playing the game, hitting the ball and getting predictable stimulation, is inherently creating more predictable environments."

This has some really intriguing possibilities, especially in artificial intelligence and computing. The human brain, containing around 80 to 100 billion neurons, is way more powerful than any computer, and our best computers struggle to replicate it. Our best effort yet required 82,944 processors, a petabyte of main memory and 40 minutes to replicate just one second of the activity of one percent of the human brain.

If the architecture is more like that of an actual brain – perhaps even a synthetic biological system like the one developed by Kagan and colleagues – this goal may not be quite so far out of reach.

But there are other, perhaps more immediate implications.

For example, DishBrain might be able to help chemists understand the effects of various medications on the brain, to a cellular level. It might, one day, even help tailor medications to a patient's specific biology, using neurons cultured from stem cells reverse engineered from that patient's skin.

"The translational potential of this work is truly exciting: it means we don't have to worry about creating 'digital twins' to test therapeutic interventions," says Friston. "We now have, in principle, the ultimate biomimetic 'sandbox' in which to test the effects of drugs and genetic variants – a sandbox constituted by exactly the same computing (neuronal) elements found in your brain and mine."

For now, the next step is to figure out how DishBrain's ability to play Pong is affected by drugs and alcohol. "We're trying to create a dose response curve with ethanol – basically get them 'drunk' and see if they play the game more poorly, just as when people drink," Kagan says.

In other words, a dish of brain cells rolls into a bar…

The team's research has been published in Neuron.

Wait, hold up...when can we party with Dishbrain??

Last edited:

How many brain cells does it take to type "I'm just a pile of brain cells in a dish but I fucked your mum last night" into a chat box?Behold! Bask in the synthetic majesty of ...DISHBRAIN!

(Absolutely ripe material for the next sci-fi horror dystopian novel/film/videogame story)

WATCH: A Dish of Brain Cells Figured Out How to Play Pong in 5 Minutes

How many brain cells does it take to play a video game? No, really.www.sciencealert.com

~insane in the dishbrain~

Wait, hold up...when can we party with Dishbrain??

View attachment 7181

Yeah, this is how we science in Australia.

During the Victorian Era, it was really popular for rich people to buy dead Egyptians and do weird things with their bodies. Using them as paint had been around for centuries, though the demand meant they'd often make new mummies out of criminals and then grind them up.

There are truly no limits to where the partying starts.

There was a legit VR edition made for Doom 3 in 2021. It costs about 20 bucks and actually doesn't look half bad. The reviews aren't great, but considering somebody just took the original Doom 3 and hit it with a wrench until it fit in VR, and even made the effort to clean it up a bit to work better, I think it's pretty solid.

Just seems kind of nice, especially because I cannot possibly imagine Bethesda expected to actually make money on this. Just seems like something people did in service of the ancient victory cry of "I got Doom to run on this".

Just seems kind of nice, especially because I cannot possibly imagine Bethesda expected to actually make money on this. Just seems like something people did in service of the ancient victory cry of "I got Doom to run on this".

Negative as in 'No! Don't keep mailing us your poo!"?As for me, I did the "poop in a bucket and mail it out" test. Just got the results today: Negative.

Well, they didn't specify....Negative as in 'No! Don't keep mailing us your poo!"?

The more you know...

www.snopes.com

www.snopes.com

No, the Right to Vote Isn't in the US Constitution

The framers of the Constitution never mentioned a right to vote. They didn’t forget. They intentionally left it out.

All those frothing nationalists treating the Constitution as some divine god-given infallible tome don't ever mention this quirky lil feature. How strange.If you’re looking for the right to vote, you won’t find it in the United States Constitution or the Bill of Rights.

Two of the most important cases at the Supreme Court this year address voting rights, and both legal controversies focus on the right to vote. But rather than denials of the right to cast a ballot, they address the more subtle forms of manipulation grounded in how votes are counted. Underlying the public discussion of these election law controversies, and many others, is a misunderstanding about the Constitution: the assumption that the right to vote is clearly protected.

Moore v. Harper questions the constitutionality of attempts to rein in partisan gerrymandering, manipulation of the geographic boundaries of electoral districts to advantage the party controlling the map. Merrill v. Milligan deals with racial gerrymandering, which changes electoral boundaries to advantage one race over another.

The Bill of Rights recognizes the core rights of citizens in a democracy, including freedom of religion, speech, press and assembly. It then recognizes several insurance policies against an abusive government that would attempt to limit these liberties: weapons; the privacy of houses and personal information; protections against false criminal prosecution or repressive civil trials; and limits on excessive punishments by the government.

But the framers of the Constitution never mentioned a right to vote. They didn’t forget – they intentionally left it out. To put it most simply, the founders didn’t trust ordinary citizens to endorse the rights of others.

They were creating a radical experiment in self-government paired with the protection of individual rights that are often resented by the majority. As a result, they did not lay out an inherent right to vote because they feared rule by the masses would mean the destruction of – not better protection for – all the other rights the Constitution and Bill of Rights uphold. Instead, they highlighted other core rights over the vote, creating a tension that remains today.

Relying on The Elite to Protect Minority Rights

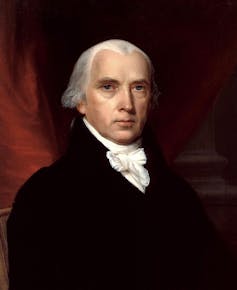

James Madison of Virginia.White House Historical Association/Wikimedia Commons

Many of the rights the founders enumerated protect small groups from the power of the majority – for instance, those who would say or publish unpopular statements, or practice unpopular religions, or hold more property than others. James Madison, a principal architect of the U.S. Constitution and the drafter of the Bill of Rights, was an intellectual and landowner who saw the two as strongly linked.

At the Constitutional Convention in 1787, Madison expressed the prevailing view that “the freeholders of the country would be the safest depositories of republican liberty,” meaning only people who owned land debt-free, without mortgages, would be able to vote. The Constitution left voting rules to individual states, which had long-standing laws limiting the vote to those freeholders.

In the debates over the ratification of the Constitution, Madison trumpeted a benefit of the new system: the “total exclusion of the people in their collective capacity.” Even as the nation shifted toward broader inclusion in politics, Madison maintained his view that rights were fragile and ordinary people untrustworthy. In his 70s, he opposed the expansion of the franchise to nonlanded citizens when it was considered at Virginia’s Constitutional Convention in 1829, emphasizing that “the great danger is that the majority may not sufficiently respect the rights of the Minority.”

The founders believed that freedoms and rights would require the protection of an educated elite group of citizens, against an intolerant majority. They understood that protected rights and mass voting could be contradictory.

Scholarship in political science backs up many of the founders’ assessments. One of the field’s clear findings is that elites support the protection of minority rights far more than ordinary citizens do. Research has also shown that ordinary Americans are remarkably ignorant of public policies and politicians, lacking even basic political knowledge.

Is There a Right to Vote?

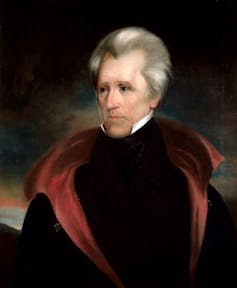

Andrew Jackson of Tennessee.Ralph Eleaser Whiteside Earl/Wikimedia Commons

What Americans think of as the right to vote doesn’t reside in the Constitution, but results from broad shifts in American public beliefs during the early 1800s. The new states that entered the union after the original 13 – beginning with Vermont, Kentucky and Tennessee – did not limit voting to property owners. Many of the new state constitutions also explicitly recognized voting rights.

As the nation grew, the idea of universal white male suffrage – championed by the commoner-President Andrew Jackson – became an article of popular faith, if not a constitutional right.

After the Civil War, the 15th Amendment, ratified in 1870, guaranteed that the right to vote would not be denied on account of race: If some white people could vote, so could similarly qualified nonwhite people. But that still didn’t recognize a right to vote – only the right of equal treatment. Similarly, the 19th Amendment, now more than 100 years old, banned voting discrimination on the basis of sex, but did not recognize an inherent right to vote.

A voter casts a ballot at a mobile voting station in California in May 2020.AP Photo/Marcio Jose Sanchez

Debates About Voting Rights

Today, the country remains engaged in a long-running debate about what counts as voter suppression versus what are legitimate limits or regulations on voting – like requiring voters to provide identification, barring felons from voting or removing infrequent voters from the rolls.

These disputes often invoke an incorrect assumption – that voting is a constitutional right protected from the nation’s birth. The national debate over representation and rights is the product of a long-run movement toward mass voting paired with the longstanding fear of its results.

The nation has evolved from being led by an elitist set of beliefs toward a much more universal and inclusive set of assumptions. But the founders’ fears are still coming true: Levels of support for the rights of opposing parties or people of other religions are strikingly weak in the U.S. as well as around the world. Many Americans support their own rights to free speech but want to suppress the speech of those with whom they disagree. Americans may have come to believe in a universal vote, but that value does not come from the Constitution, which saw a different path to the protection of rights.

Morgan Marietta is a Professor of Political Science at UMass Lowell.