ChatGPT Looms Over the Peer-Review Crisis

Research shows that academics might be using generative AI tools to cut corners on a fundamental pillar of the scientific process.

404 Media is a journalist-owned website. Sign up to support our work and for free access to this article. Learn why we require this here.

Nicholas LoVecchio told me he knew something was wrong as soon as he received the peer-review responses to his paper about “taboo” language titled “Using translation to chart the early spread of GAY terminology.”

“I received them in the evening, the week before Christmas and I was just going through them in disbelief,” LoVecchio told me on a call, referring to the responses to his paper from two anonymous peer reviewers for the journal

mediAzioni. “It basically didn't say anything, they didn't really say anything of substance. At that point I actually hadn't used ChatGPT but I’m very familiar with what it sounds like.”

LoVecchio ran the responses through seven AI-generated text detectors, all of which indicated a high likelihood that they were AI-generated.

mediAzioni denies that the responses were AI-generated, and so did the anonymous reviewers, who responded to LoVecchio’s accusations.

“The machine content was obvious to me because there was not a single coherent critique that meaningfully engaged with my paper,” LoVecchio wrote on his personal

website late last year. On our call, he told me the responses were generic, and simply told him he needed to cite more sources and to work on his transitions, which he said was “preposterous.”

“I went through the reports line by line, word by word: there was nothing there,” he wrote on his site.

"From the assessments made and the consistency of the reviews, we are certain that we can exclude that they were carried out by means of generative AI systems such as GPT-3 and GPT-4," Chiara Elefante, Raffaella Baccolini, and Delia Chiaro, the co-directors of

mediAzioni, told me in an email. "While we are aware that it can be hard to identify whether such tools were adopted, we firmly believe that the form and content of the two reviews is the work of human beings. The journal intends to closely follow the emerging issue of generative AI and scientific publications."

404 Media can’t confirm whether the peer-reviews were AI-generated, but even if LoVecchio is wrong, his suspicion speaks to a much larger problem in academic publishing that makes it an especially vulnerable target for ChatGPT and other large language models.

For years, researchers have warned that they are stretched too thin to properly carry out the labor involved in one of the most important pillars of the scientific process: peer-review. Ironically, as a number of

academic papers have argued, the problem is that more academics are asking for peer reviews than there are willing and available peer reviewers. Researchers have a professional incentive to publish papers, but peer review is often unpaid, time-consuming work. A 2018

report on the global state of peer review found that in 2013, editors at journals had to invite an average of 1.9 reviewers to get one review done. By the end of 2017, that number increased to 2.4 invitations for every completed review. The same report also found that it takes a reviewer a median of 16.4 days to complete a review after agreeing to the assignment.

It is a mostly text-based task that in one way seems like it was tailor made for ChatGPT. Reviewers need to read the submitted paper and provide constructive feedback. According to a paper titled “

Monitoring AI-Modified Content at Scale: A Case Study on the Impact of ChatGPT on AI Conference Peer Reviews,” which is currently submitted for peer review, between 6.5 and 16.9 percent of peer reviews submitted to a number of AI conferences “could have been substantially modified by LLMs.”

404 Media

recently found many AI-generated papers published in academic journals, but these were smaller, less known publications, and likely “paper mills” that will publish anything for a price. The authors of the AI conference peer review study did not find similar spikes in AI-generated text in 15

Nature journals.

“In fact, some of my colleagues are telling me that these numbers are probably underestimating what they have expected,” Weixin Liang, the lead author of that paper and a PhD computer science student in Stanford University, told me on a call.

Christopher MacLellan, an assistant professor at the School of Interactive Computing College at the Georgia Institute of Technology, told me that he’s asked to do peer reviews three to five times a year, but that he has a self-imposed quota of doing one or two peer reviews a year, “so that I can stay sane.”

“The bigger issue is that there's just the peer review crisis you're talking about where there's just so many papers being sent to these conferences,” he said. “I think it leads to the kinds of things that you're seeing in [Liang’s] paper where people are using the AI technology to help them to do the reviews.”

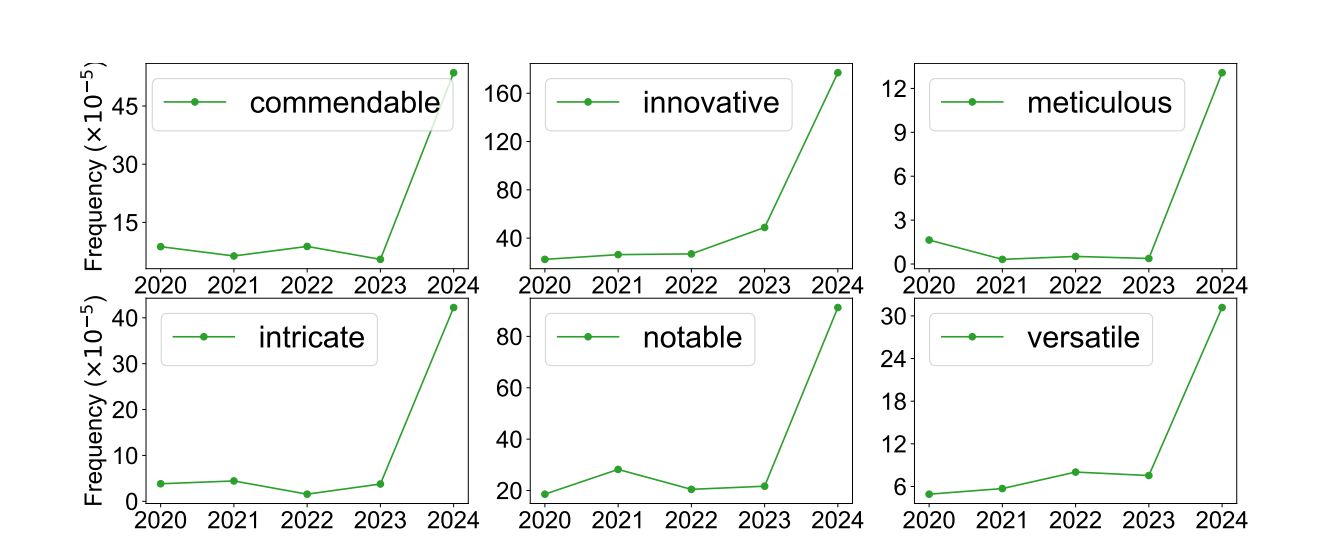

Liang’s method attempts to detect AI-generated text differently than the free online tools LoVecchio had used to test the peer reviews he received. Rather than feeding a single piece of text to an LLM that was trained to detect AI-generated text, Liang and his co-authors created a large corpus of peer reviews from the AI conferences ICLR 2024, NeurIPS 2023, CoRL 2023, and EMNLP 2023. They then tracked the usage frequency of specific adjectives that occur disproportionately more frequently in AI-generated texts than in human-written reviews such as “meticulous,” “intricate,” and “innovative.” Their study found “a significant shift in the frequency” of these adjectives, pointing to a growing use of AI-generated text in peer reviews. Importantly, the percentage of AI-generated text the paper argues it detected (between 6.5 and 16.9 percent) points to the likely amount of AI-generated text in the entire corpus, and can’t reliably point to specific papers that used AI to generate text.

A CHART FROM "MONITORING AI-MODIFIED CONTENT AT SCALE" SHOWING A SHIFT IN ADJECTIVE FREQUENCY IN ICLR 2024 PEER REVIEWS.

A CHART FROM "MONITORING AI-MODIFIED CONTENT AT SCALE" SHOWING A SHIFT IN ADJECTIVE FREQUENCY IN ICLR 2024 PEER REVIEWS.

“The circumstances in which generated text occurs offer insight into user behavior: the estimated fraction of LLM-generated text is higher in reviews which report lower confidence, were submitted close to the deadline, and from reviewers who are less likely to respond to author rebuttals,” they write in the paper. In other words, it looks like peer reviewers are more likely to resort to using AI to generate peer reviews as the deadline gets closer and they’re running out of time.

Liang told me that it’s too soon to pass value judgments to say that using LLMs in peer reviews is good or bad, but that one clear concern is the homogenization of feedback.

“Normally for each paper, you have three reviewers, so you've got three reviews from different backgrounds,” Liang said. “And if all of the reviewers are using the same ghost writer then you've got less diversity of thought, you've got content that is more homogenized because they're using similar large language models to modify or even substantially generated text. And then you probably have biases that you don't know were secretly sneaking into the [peer reviews].”

LoVecchio said he saw AI-generated peer reviews as a much bigger problem already.

“Peer review is seen as fundamental to science,” he said. “It's seen as the building block of knowledge creation and scholarship [...] My point was never that my paper was perfect. It was a first draft, I was actually open to changes, I made tons of changes myself before posting the paper online. But I was not willing to take part in what I saw as a charade.”

Again, 404 Media could not verify that the peer reviews LoVecchio received were AI-generated. We’ve reviewed his correspondence with

mediAzioni, which said his accusations are “unsubstantiated and without merit.”

mediAzioni also declined LoVecchio’s request to deanonymize the reviewers, but they did pass on his complaints to the two reviewers, who then provided LoVecchio with their own responses. 404 Media has viewed these responses (which LoVecchio says are substantially different in content and style than the original peer reviews, and that AI detection tools did not find to be AI-generated) as well, in which one reviewer says the accusation that he used AI to generate his review was “totally misplaced,” and the other says “I am very much human and not a machine.”

In their responses to LoVecchio’s accusations, both reviewers note that they are not native English speakers. “I’ve learned and emulated the language patterns of native speakers in the academic context of practice, and this might be the reason why the software is underlining that I am not human,” one reviewer wrote.

Regardless of what actually happened with LoVecchio's paper, the specter of ChatGPT looms over the peer review and academic writing process. In this way, it's similar to what we've seen with deepfakes and AI generated imagery. The mere existence of deepfakes and AI images are regularly used to discredit actual photos and videos, and have created a situation where people have begun to question the "realness" of everything.

Liang told me that the type of AI detection tools LoVecchio used are particularly bad at falsely identifying text from non-native English speakers as being AI-generated for the exact reason the reviewer points out.

“Non-native English speakers have less diverse vocabulary to use, they use less diverse sentence structures,” Liang said. “Because they are English learners they don't know that many different ways of writing yet, they probably know the most common rules and that helps them to write.”

LLMs by default also produce text that is more generalized, and uses common structures and vocabulary, so AI detectors are more likely to falsely detect these non-native English writers as AI-generated.

“I am sympathetic to this argument and it's kind of the thing that makes me most uncomfortable in my position because I am a mother tongue English speaker and here I am making my own accusations against reviewers who are not mother tongue English speakers,” LoVecchio said.

Whether LoVecchio’s peer-reviews were AI generated or not doesn’t change the fact that the peer review process is in a crisis which predates the advent of easily accessible generative AI tools.

“Many people have been talking about this even before ChatGPT came out,” Liang said “If you look at the number of submissions to those major AI conferences over the years, you see a pretty substantial increase, but you don't have an increase of experienced reviewers at that scale. So what happens is people are being burned out. That is a long known problem in the community. That’s probably one reason why people are using the help of LM to accelerate their writings.”

Several papers published just this year are studying the use of AI-generated text in academia, and found that more standards and transparency about their use are needed.

MacLellan said that he can imagine one way to fix the peer review crisis is to create a kind of credit system, where researchers have to do a number of reviews before they can submit paper to a journal or conference.

In LoVecchio's eyes, the peer review process is broken, and has to change.

“I really think that the answer to the huge pressures of peer review, the workload, the stresses—I think the answer is just to rethink the process radically,” he said. “In the future, I just have trouble seeing that I would ever allow anything of mine to be reviewed in blind peer review, I just don't believe in it anymore. After this, I'll have to move to open peer review.”