Which will never happen.It's one of the biggest budget items, and as such is a juicy target. But it's also super important to a huge chunk of their base, which means they can't do anything to it unless and until they don't need old folks voting for them to stay in power any more.

US 2024 Presidential Election

- Thread starter gorfias

- Start date

I mean, once the Boomers finish dying off old folks will be a much smaller share of the voter base, the old folks to follow them have done less drifting right over time than their parents, and the youth has been leaning more right than usual so it may be a thing they can get away with in a decade or two, presuming none of the "end of fair elections" doomsaying turns out to be accurate (in which case they could do it faster).Which will never happen.

The next generation is getting close to retirement. It's really only the young people (under 30, maybe under 40) that might not care about social security. It's still gonna be well over half the voter base because you can't vote for about the 1st 20 years, a higher percentage of young people don't vote IIRC. You can't get rid of social security and not massively lose several election cycles in a row. The democrats were removing people from elections...I mean, once the Boomers finish dying off old folks will be a much smaller share of the voter base, the old folks to follow them have done less drifting right over time than their parents, and the youth has been leaning more right than usual so it may be a thing they can get away with in a decade or two, presuming none of the "end of fair elections" doomsaying turns out to be accurate (in which case they could do it faster).

Shocked, shocked, to find gambling in this casino.

Armored Teslas would have, what, a 50 mile range per charge and 200 miles to spontaneous combustion?

That document was last updated under the Biden Administration. I'm not saying that proves that Elon had nothing to do with, and it could still be some major money laundering, but there is also a potential world where DOGE comes in and actively cancels a giant payout to Tesla recommended by the previous administration.

Shocked, shocked, to find gambling in this casino.

Armored Teslas would have, what, a 50 mile range per charge and 200 miles to spontaneous combustion?

I hate that I can't just trust video since it is The Internet Dot Com but I've been seeing the video from multiple sources now so I'm going with it, if for any other reason, it's funny.

Kids say the darndest things!

Ah so they tryng to min max psychopathy to see how far they can push their followers' cognitive dissonance. Methamphetamine clouds Elon's gurnballs from the obvious: follower brains have long since broken I'm afraid, might as well tell them to walk back into the sea for the lols as it's clearly more merciful a fate than their current sadomasochistic orgy. Or have we yet to endure their version of Hannibal convincing a guy to peel his own face off with a shard of glass first? Scale it up, as they say.

In Egypt, US Has Slashed Humanitarian Aid But Maintained Military Spending

Though USAID helped some Egyptians, it also always put “America first,” local development sector workers say.

In Egypt, US Has Slashed Humanitarian Aid But Maintained Military Spending

Though USAID helped some Egyptians, it also always put “America first,” local development sector workers say.

By Marianne Dhenin , TruthoutPublishedFebruary 12, 2025

A member of the Egyptian-Qatari security forces watches from an observation post as displaced Palestinians cross the Netzarim Corridor toward the north, following the withdrawal of Israeli troops in central Gaza, on February 10, 2025.SAEED JARAS / Middle East Images/AFP via Getty Images

Across the globe, communities are still reeling from the sudden cutoff of U.S. funding for food aid, vaccination programs, education, disability supports and more.

The State Department issued guidance freezing foreign assistance for at least a 90-day period on January 25, throwing programs funded with U.S. foreign aid into turmoil worldwide. As a result, an estimated $500 million in food aid is reportedly “at risk of spoilage as it sits in ports, ships and warehouses,” CBS reports, and $8.2 billion in unspent humanitarian aid is now adrift without tracking or oversight.

Companies that contract with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) filed a lawsuit against the Trump administration on February 11 over its attacks against the agency, adding to lawsuits already filed by government workers and nonprofit organizations. On the same day, Democrats in Congress introduced a bill aimed at halting the elimination of USAID, but it faces an uphill battle in the Republican-controlled House and Senate. Meanwhile, Republicans from Kansas are now trying to move the food aid portion of USAID’s work to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The freeze in U.S. foreign assistance has created particular tumult among longstanding top aid recipients such as Egypt. Weapons support to Egypt was one of the only disbursements exempted from the funding freeze, and this money continues to flow despite criticism of the nation’s human rights record. But projects in public health, public administration, education and agriculture have come grinding to a halt in the North African country, and thousands of Egyptian students and workers now face uncertain futures.

“It’s been very, very unclear. It was just ‘stop working’ and nothing else,” said Laila Ayman, an independent consultant in Egypt’s development sector. “They did not even give a couple of days’ notice for activities to wrap up or for people to sort out transportation back home.”

Truthout spoke to 11 Egyptian students and workers affected by the funding freeze about how their lives have changed due to the State Department order and about what they think may come next for them and their nation, which has been among the top recipients of U.S. foreign aid since the 1980s. Most of those interviewed were notified that the funding needed to pay their wages or tuition fees was no longer available within hours of the news of the funding freeze. Many chose to speak anonymously for fear of jeopardizing their funding agreements if foreign aid were to resume following the current suspension.

While Egypt is among the top recipients of U.S. foreign aid, the bulk is provided in the form of military aid. Congress placed conditions on some of Egypt’s military aid in 2008 in an attempt to compel the nation to strengthen its democratic institutions, release political prisoners and allow civil society organizations, human rights defenders and the media to function without interference. More than 15 years later, however, the number of political prisoners held in Egyptian jails has grown to an estimated 60,000, and human rights activists and journalists remain common targets of state repression.

Of a total disbursement of $1.5 billion in aid to Egypt in 2023, the most recent year for which full reporting is available, about $1.2 billion was military aid. Last year, the Biden administration sent $1.3 billion in military aid to Egypt, ignoring the conditions placed on a portion of the funds by Congress over human rights concerns. Then-Secretary of State Anthony Blinken cited Egypt’s role as a mediator between Israel and Hamas as a reason for waiving those conditions. Only Israel received more military aid than Egypt last year to fund its ongoing occupation of Palestine and genocide in Gaza.

The Trump administration’s decision to continue arms support while halting other foreign aid to Egypt struck Ayman as a power play. “If Trump was really interested in not spending any more U.S. money, then he should have also cut the military aid,” Ayman said. “This is all a way to exert pressure on Egypt to fall in line, and not just Egypt, but the whole world.”

Egypt has long been a strategic ally of the U.S., operating as a broker between U.S. interests, the Israeli government and Palestine, which borders Egypt to the east. Trump’s ambitions to ethnically cleanse Palestinians from the Gaza Strip and colonize the territory, announced in a press conference alongside Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu on February 4, cannot move forward without Egypt’s involvement. The Egyptian government has thus far rejected such ideas, calling Trump’s most recent proposal a “blatant violation” of international law.

Some of the funding freeze’s most high-profile effects have come from disruptions to USAID, the world’s single largest provider of humanitarian assistance — while often also serving as “the friendly side of US interventionism.” Since coming to power as commander of Trump’s new Department of Government Efficiency, unelected billionaire Elon Musk has made the agency’s destruction a pet project.

Students at 13 public and private universities in Egypt were among those affected by the dismantling of USAID. Over a thousand college students from across Egypt who receive scholarship funding via USAID were at the American University in Cairo (AUC) for the first day of a two-week pre-semester skills development camp when the news came: Due to the State Department’s order, the remainder of the camp was canceled, and the future of their funding was uncertain.

“Some of [the students] were panicking, some of them were crying — it was a mess,” said one of the scholarship recipients. Following the announcement, students were given mere hours to leave their dorm rooms or hotels and return home without financial or logistical support. For some, navigating Cairo alone or financing a bus or train ticket home was challenging.

The affected scholarship programs target students from low-income backgrounds and students with disabilities. Additionally, USAID provides direct funding to Egypt’s Ministry of Education and supports centers for career development and disability services centers on several campuses nationwide.

One USAID scholarship recipient enrolled at AUC told Truthout the funding promised a brighter future for himself, his widowed mother and his siblings. “It was a dream for all of us,” he said. “We cannot afford the tuition fees at AUC, and this scholarship opportunity is a big achievement and gives us hope that I’m going to be something in the future.”

Another scholarship recipient, speaking about the program’s support for their colleagues with disabilities, said that for many, “This is the only option, the only way for them to continue studying.” One disabled student told Truthout that without the scholarship, they would be unable to access accommodations needed to allow them to continue their education. Without it, they said, they faced leaving their college altogether.

“It is not just about individual students and families,” added another affected student. “It poses a threat to Egypt’s future because these scholarships are vital to developing the next generation of leaders, scientists and innovators.”

A former college instructor, who now works in the development sector, told Truthout the decision to continue disbursements for weapons while halting support for education upset many. “It’s horrible. Instead of sending us arms all the time, at least don’t stop the education funds. Stop the arms funds, for God’s sake.”

Since students were notified of the funding disruption two weeks ago, the Egyptian Ministry of Education and individual colleges and universities have committed to closing the funding gap for many of the affected students this semester, allowing them to continue their education while awaiting news of the future of U.S. foreign aid after the ordered 90-day freeze. On some campuses, however, only continuing students are receiving support, leaving incoming first-year students with the untenable option of covering their own tuition fees and living expenses or sitting out the semester. None of the students interviewed by Truthout said they had access to the funds needed to continue their education without their scholarships.

For development sector workers, disruptions due to the funding freeze were also abrupt. Bahey Amin, a policy analyst working on a USAID-funded project, said he and his colleagues received a stop work order via email on January 28. “We are currently not receiving our salaries, we are prohibited from using email, [and] we cannot access the office in Egypt; it’s closed,” he told Truthout.

Before being furloughed, Amin worked on a public sector reform project. The project aligned with Egypt’s Sustainable Development Strategy and the stated mission of U.S. policy in the nation, which, according to the State Department’s website, last updated in 2022 during the Biden administration, is “to promote a stable, prosperous Egypt, where the government protects the basic rights of its citizens.”

The funding freeze threatens progress made toward these goals. “We are pretty much abolishing everything we have achieved,” Amin told Truthout. “Our products and achievements could be thrown in the trash can just like that within a couple of months.”

Ayman, the development consultant, told Truthout that this is not the first time the U.S. government’s actions have differed from the relatively rosy stated aims of its development programs. “What is written out there completely contradicts what’s happening on the ground,” she said.

Foreign aid programs tend to offer the highest paying jobs to foreign workers and source expertise from abroad, marginalizing local expertise and neglecting opportunities to build capacity on the ground. The conditions of many funding agreements also serve to exert significant economic and political influence over recipients. Ayman also told Truthout that on many projects, the agreements are such that the donor owns project outputs, making any progress difficult to build upon or even maintain. “This way, we’re dependent. We don’t really own the products or the services,” she said.

While the sudden funding freeze exacerbates the issue, Ayman said U.S. funding to Egypt has always put “America first.” “They give it to us for a reason because they get something out of it,” whether that’s Egypt’s cooperation in securing U.S. interests in the ongoing occupation of Palestine or the wider region, or Egypt’s role in maintaining unfettered access to the Suez Canal, one of the world’s most important shipping routes. “It’s not just charity,” said Ayman.

As the development sector reels from current disruptions, Egyptians working in the field expressed a desire to localize their efforts and become less dependent on U.S. foreign aid going forward. The current crisis has shown how contingent this funding can be. Whether or not it resumes, Ayman said, “We need to shift from the idea that the donor owns everything to, ‘No, I own it.’ We have to support capacity building and not just a complete takeover, where once a project is done, the donor takes their stuff and goes. I want us to be the ones developing the program, owning it, and training to deliver the programs to our people.”

Step One: Acknowledge the constitutional crisis. What’s Step Two? | Press Watch

Political journalists need to be prepared to dramatically change their behavior

presswatchers.org

presswatchers.org

Last edited:

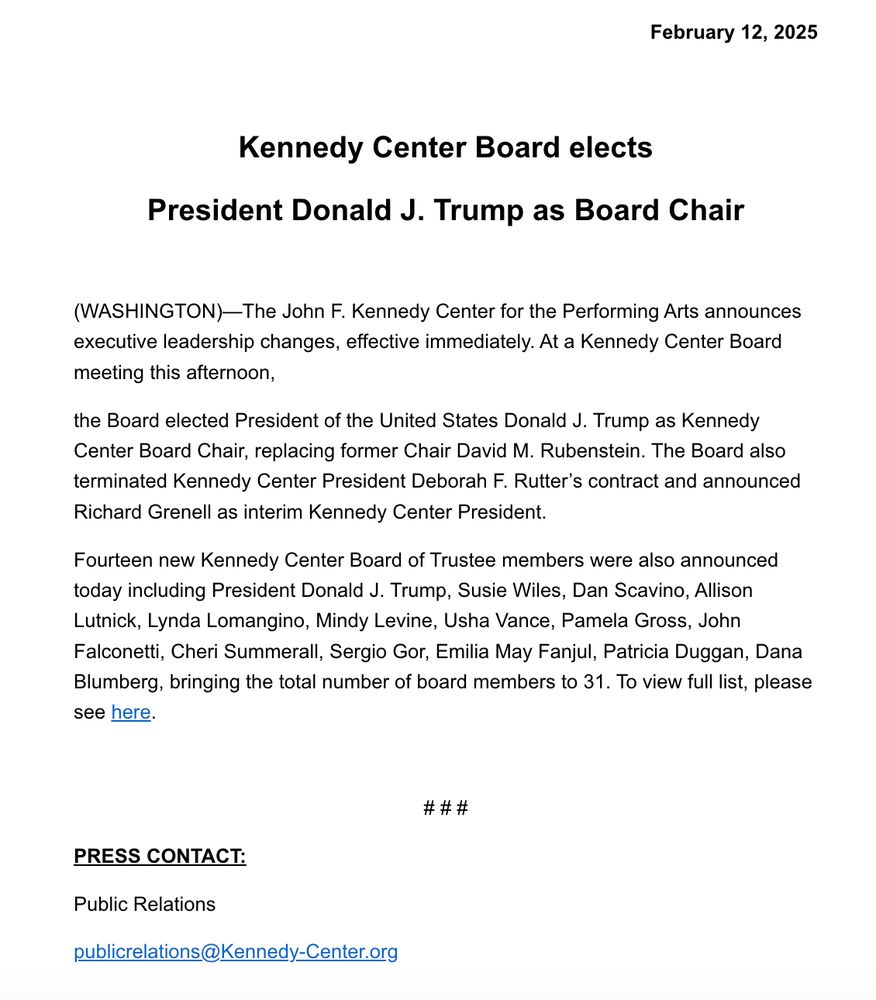

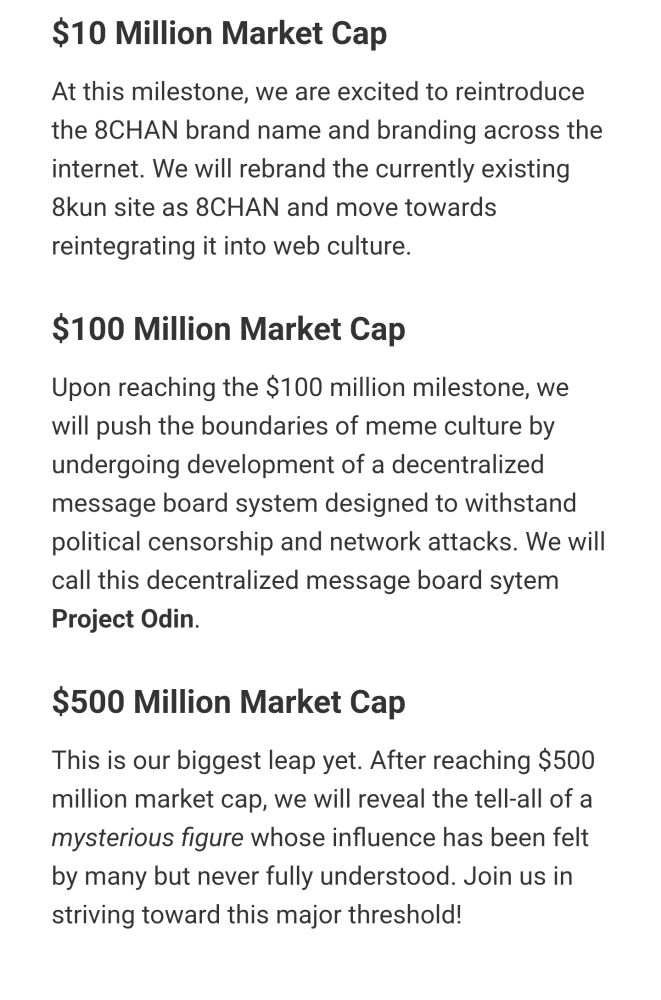

I honestly don't believe they were Q all along. I think they were Q starting from around when Q moved to 8chan or maybe slightly later, but I don't believe they were the original Q.

EDIT: Want to be more specific. So, 4chan/8chan have this thing called tripcodes, where you supply a password and it salts and hashes it and shows the result by your post. The idea is that since you don't have an account per se and can change the name you post as at will, it acts as a form of attestation that the user behind two or more posts are probably the same user.

If you look at the pattern of Q posts for each tripcode, you see a pattern that looks like what you'd expect if about a half dozen people were Q semi-interchangeably (different ones more dominant at different times, but never a single tripcode long term and never exclusively or near-exclusively one code for more than a month or two) until September 2018, after which virtually all Q posts come from one tripcode for several months then virtually all Q posts come from one other tripcode afterwards, with the tripcode switching at the same time 8chan changed their salt (which necessarily changes the result of the hash).

My personal belief is that once we switch to essentially one tripcode behind Q, that's when Watkins became Q. Before that it was probably several conspiracy trolls building on a shared mythology with each having partly overlapping periods of high activity and then mostly wandering off to do other things.

Last edited:

Musk wants to "delete entire agencies" of the Federal government.

After all, those agencies don't benefit Musk, so why even have them?

Next up on the chopping block: NASA.

I'm calling it now: NASA gets deleted; Trump declares SpaceX America's official space agency.

After all, those agencies don't benefit Musk, so why even have them?

Next up on the chopping block: NASA.

I'm calling it now: NASA gets deleted; Trump declares SpaceX America's official space agency.

So how long of this nonsense until there's either a coup to depose Trump or he'll otherwise have an ''accident''Musk wants to "delete entire agencies" of the Federal government.

After all, those agencies don't benefit Musk, so why even have them?

Next up on the chopping block: NASA.

I'm calling it now: NASA gets deleted; Trump declares SpaceX America's official space agency.

Trump moves to slap tariffs on nearly every nation, boosting trade war

In an escalation of his trade war, President Donald Trump moved to put tariffs on nations that levy taxes and fees that hurt U.S. businesses.

eu.usatoday.com

- We will put a tariff on any country who tariffs us, if for example Brazil has a tariff on ethanol, we will tariff Brazil for ethanol too.

- Any country who uses a VAT or value-added-tax system is placing a tariff on the U.S. and we will respond with tariffs against them by the same percentage as their VAT

- It will not be accepted by the U.S. to avoid tariffs by sending merchandise using a different country

- Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick has been tasked with analyzing each country's tariffs and tax systems. Lutnick will go through each country one-by-one and determine the appropriate reciprocal tariffs. Reciprocal tariffs will be added country by country as analysis is done.

- "May take a few weeks because there's a lot of data to analyze"

Trump says Canada ‘serious contender’ to be 51st state: ‘They need our protection’

Trump, 78, has repeatedly floated the idea of Canada joining the Union since his election victory Nov. 5.

Musk Staff Propose Bigger Role for A.I. in Education Department

A new chatbot would answer questions from student borrowers. The idea comes from staffers with ties to the tech industry as they push further into the agency’s work.

Senate Press Gallery (@senatepress.bsky.social)

The #Senate voted to confirm @RobertKennedyJr to be Secretary of HHS by a vote of 52:48; McConnell voted no.

So, the fascists will be driving really stupid looking cars that explode randomly when chasing someone?

Shocked, shocked, to find gambling in this casino.

Armored Teslas would have, what, a 50 mile range per charge and 200 miles to spontaneous combustion?

I need to apologise to a fair few not very good dystopian sci-fi films.

This is fine. It's what America voted for.From the press conference:

Trump moves to slap tariffs on nearly every nation, boosting trade war

In an escalation of his trade war, President Donald Trump moved to put tariffs on nations that levy taxes and fees that hurt U.S. businesses.eu.usatoday.com

Thus even it turns out that they don't like it and it's bad for them, they deserve it anyway.

I don't know why he's complaining; this is what he's always wanted- a big tough strongman to make the rest of us live the way he thinks we ought.When Mitch McConnell is the voice of reason, we're all fucked.

Also, he keeps falling down but missing the big pit leading directly to Hell that's been waiting for him.

- Feb 13, 2009

- 178

- 41

- 33

- Country

- United Kingdom

- Gender

- Does it really matter?

1. Nearly the entire world uses VAT in some form or the other. This is just an excuse for him to slap tariffs on everything.

- Any country who uses a VAT or value-added-tax system is placing a tariff on the U.S. and we will respond with tariffs against them by the same percentage as their VAT

2. How the hell is the VAT I pay on, let's say my quarterly haircuts, ripping the US off?

You know this happened under Biden right? You know this happened because the left wants zero emission vehicles and guess who's literally the only company that makes this type of vehicle and the only one that even bid on the contract?

Shocked, shocked, to find gambling in this casino.

Armored Teslas would have, what, a 50 mile range per charge and 200 miles to spontaneous combustion?

That's just how Trump does business. That's not even a joke. It just is.1. Nearly the entire world uses VAT in some form or the other. This is just an excuse for him to slap tariffs on everything.

2. How the hell is the VAT I pay on, let's say my quarterly haircuts, ripping the US off?

I'm not 100% sure, but I think it's like this:2. How the hell is the VAT I pay on, let's say my quarterly haircuts, ripping the US off?

Sales tax only hits the end product sold to consumer. Nothing is taxed in production right up to the point the retailer makes the final sale, and the product is then taxed.

VAT, however, is applied at every step in the process. So a mining firm sells some raw materials to a manufacturer, and tax is paid on the value of the materials. The manufacturer turns the materials into a gizmo, sells it to a retailer, and tax is applied on the value added in that step (difference between raw materials and gizmo price). The retailer then sells to the customer, and tax is applied on the value added in that step (difference between the manufacturer price and retailer price).

So, in other words, if the USA ships something to be further worked on or sold in a country with VAT, presumably the relevant chunk of VAT is paid at the export/import step for whatever the cost is at that step. Trump/team presumably thinks is like a tariff.

But's it's absolutely not a tariff. The USA's exports are simply operating on the same level playing field as any other, because everything sold in that country, no matter where it is manufactured, is ALSO paying VAT at the same rate. Including the importing country's own production!

As far as I can tell it's just economic illiteracy from the Trump administration.