In her office in Freiburg im Breisgau, a town in the sunny southwestern corner of Germany at the foot of the Black Forest, Sarah Pohl is overwhelmed. A woman has called in distress after her husband said he would divorce her if she got vaccinated. A man has lamented that his wife refused to send the kids to school, fearing that wearing masks would damage their brains. Another woman was alarmed after her partner insisted that they migrate to

Paraíso Verde, a Paraguayan community offering newcomers a life “outside of the ‘matrix’ ” without 5G, chemtrails, and mandatory vaccinations.

Tending to such calls is Pohl’s job. A blond-haired, soft-spoken therapist in her 40s, she holds what must be one of Germany’s most peculiar taxpayer-funded jobs: She’s a counselor on cult duty.

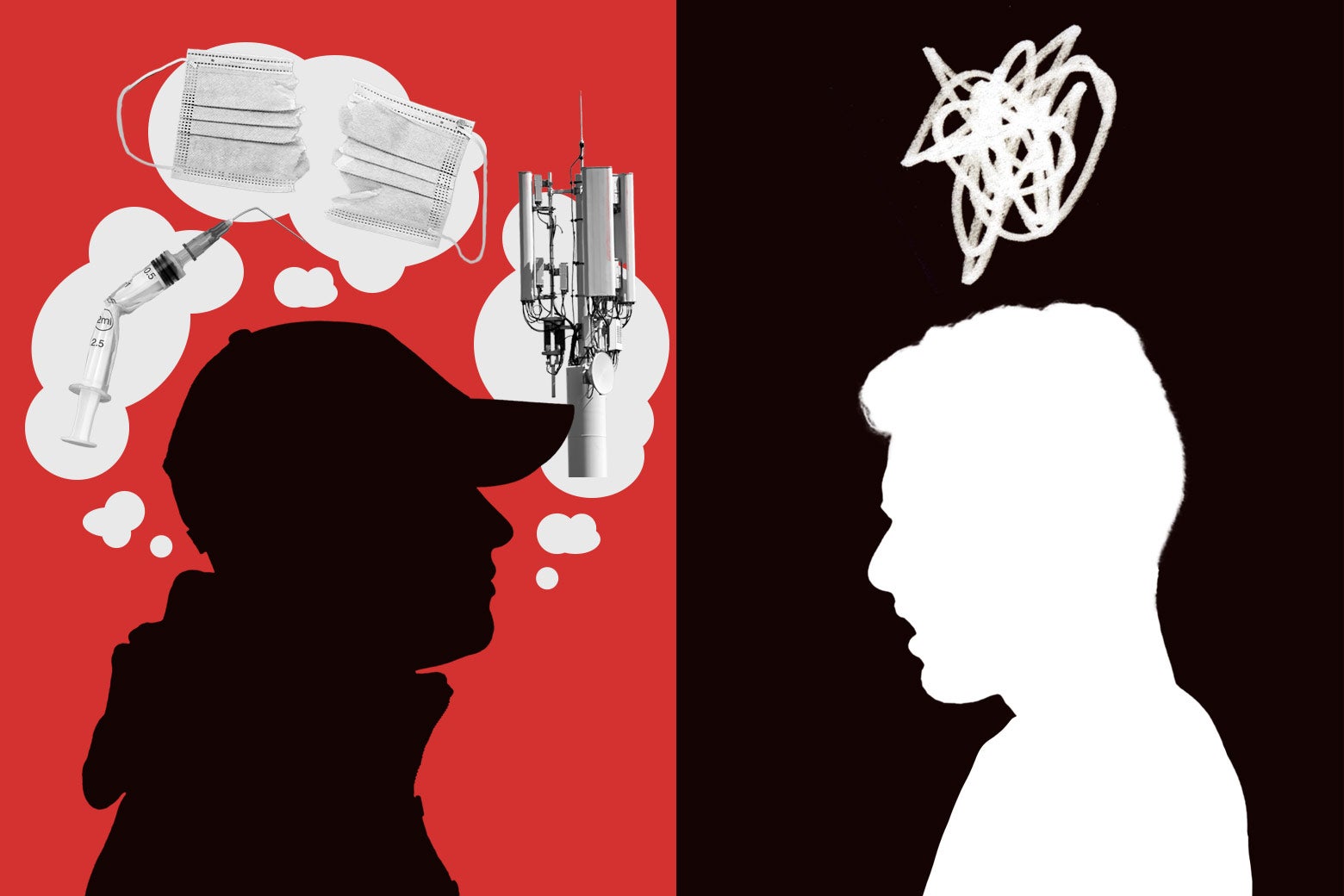

While the rest of the world tends to see German affairs as stable and even boringly predictable, in the last year and change of the Merkel era, the country has become a flashpoint for conspiratorial thinking. The majority of Germans supported the government’s handling of the pandemic, but the country also saw some of the fiercest pandemic-related protests in the world, according to

multiple media reports, with many started by a group called Querdenken, which originated near Freiburg. In August 2020 in Berlin, a few hundred protesters who believed that Donald Trump had come to the German capital to “liberate” the country even attempted to “

storm” the Reichstag. And ahead of the September 2021 general election,

theories circulated that the Green Party leader’s college degree was fake, that the floods that ravaged the country’s west in July were planned by Merkel’s government to gin up support for her party in the polls, and that mail-in ballots would lead to widespread

voter fraud.

Calls began to pour in from confused people wondering if they should break off contact with conspiracy theorist and pandemic-denying relatives or friends.

Most of these theories reached Pohl’s office. Over the course of many months, she and her four co-workers, who call their specific intervention services Zebra (there are multiple such offices by different names and with slightly different focuses in other states), came to play a distinctive role in untangling the ways pandemic-related theories have driven rifts among Germans, separating families and turning friends against one another. Pohl’s team was tasked with helping to defuse conflicts, build bridges, and mend the suffering and anxiety that so many across the West have experienced since the start of the pandemic. Their services, like those offered by the other regional offices, are free to all citizens.

Zebra (“not everything is black or white,” its website reads) was founded on Feb. 15, 2020, just a few weeks before the German government introduced the first restrictions to contain COVID-19. Michael Blume, the antisemitism commissioner of Baden-Württemberg, advised the state government to set up the center because he “predicted that digitalization would turn conspiracy myths into a great danger.” He thought of it as a public service: Whenever citizens were confused about any theories they heard or worried about a relative’s engagement with them, they had a place they could turn to, with someone who would listen and help them make sense of the situation. “Anyone who is affected by conspiracy beliefs or is in danger of losing close relatives should find open ears and advice from the state and churches,” Blume says.

At first, conspiracy theories were supposed to be only one of Zebra’s focuses, alongside other problems like cults. But the pandemic and the explosion of disinformation that accompanied it meant conspiracy theories quickly came to dominate the requests that reached Zebra. “I have never seen conflicts escalating like this,” Pohl says. As the pandemic forced people to take positions on restrictions, vaccines, and the new normal, calls began to pour in from confused people wondering if they should break off contact with conspiracy theorist and pandemic-denying relatives or friends. Frequently, after offering an initial explanation of the situation, clients would break down on the phone, asking “What should I do?”

Pohl has personal experience here. After growing up in a very religious family, she felt the pull of conspiracy theories herself. After 9/11, she remembers avidly scrolling through alternative explanations of the attack. “I would hear these theories and think,

Oh, wow, that’s interesting!” she says. “I realized how fascinating it could be to see a seemingly new world open up before your eyes.” Then, about 15 years ago, a close friend of hers who believed several conspiracy theories died by suicide. She had already been thinking about starting to advise people who might go through similar crises, and that further showed her how important such work could be. She worked for eight years in a counseling center that provided advice for people who had extrasensorial experiences—for example, people who claim to see ghosts or read minds or that they’re under a magic spell—which she says was a formative experience that helped her take this new set of tasks on. “We don’t judge,” she says. “People have different ways to explain the world to themselves. … I am more interested in understanding why they do that, and how that might fit into their life story.”

When someone calls Zebra, Pohl and her co-workers make an appointment in person, online, or via phone. Every case is different: It could end after the first meeting or the counseling could go on for months, all free of charge. “There is no one recipe we use, but we look at how bad the conflict has got,” she says. “For example, are they still talking to each other?”

In many cases, things are pretty bad. Most callers are not the conspiracy theorists themselves (those “people don’t want to be saved,” Pohl says), but people whose relationship with a conspiracy theorist family member—typically a spouse or a parent—is deteriorating rapidly. Or they might be alarmed that their loved one is becoming radicalized. They often call Zebra as a last resort: “It takes a certain amount of suffering before someone calls us,” says Pohl. “And when they do, a lot has broken down in their relationship.” This is not always ideal—”sometimes we think it would have been better if they had called earlier,” Pohl says. Often, angry and sour, callers ask Pohl to “tell my wife she’s an idiot,” or to be given figurative “ammunition” to win arguments.

But rather than trying to convince conspiracy theorists or coax them back from the brink, Zebra doesn’t pick a side in the argument and encourages callers to learn to deal with their partners’ new beliefs differently. “Often there is a lot of intolerance on both sides of the argument,” Pohl says. “Both sides get extreme because they no longer speak to each other.” Sometimes, Zebra advises callers to establish boundaries; rediscover shared interests to avoid long, sensitive discussions; or make an effort to understand the psychological reason their loved one might have turned to a conspiracy theory. Other times, it’s about shifting discussions from facts to feelings in the belief that people change through emotional experiences, not discussing ideas. Or Pohl and her colleagues try to reframe the conspiracy theories callers get upset at being bombarded with. She encourages some people to see fake news and pseudoscience as even a misunderstood form of affection. “It’s a bit like with cats,” says Pohl. “Cats sometimes bring dead mice to the people they love.”

In some cases, the results are encouraging. In April, a middle-aged man in distress called Zebra, concerned about his wife. The woman had developed crushing anxiety about vaccines and face masks; she would spend hours trawling Telegram—a messaging app that became popular among many COVID skeptics in Europe after they were banned from other social media platforms—for information about the pandemic. She was crying a lot and couldn’t sleep at night. After she started refusing to wear a mask, which she

mistakenly believed would cause blood oxygen levels to drop and make her sick for inhaling her germs, she lost her job as a physiotherapist. When he first called, the husband said his last straw was that she wouldn’t let him get vaccinated for fear he would become immunocompromised and die. He wondered if they should break up.

As they do in many cases, Pohl and her team invited the man to come in with his wife. Over several meetings, almost like couples counselors, they guided the couple to explore the reasons and feelings behind their stances. The relationship had been strained for some time, which made every disagreement turn into a fight. The woman came from East Germany, where distrust in the state is high, and had developed a “huge existential fear” after losing her parents at an early age. The man had always adjusted to his wife’s fears and was now trying to push back after a long time. Talking about their feelings helped the couple get closer to each other, Pohl says. Neither changed their opinion, but the fights slowly stopped. The man was able to get vaccinated; the wife still believes many widely debunked conspiracy theories but recognizes that the constant scrolling was harming her. She limited that, and she’s able to get a good night’s sleep again.

Preaching tolerance and openness can seem like a risky strategy at a time when, in Germany too, scores of vaccine skeptics and conspiracy theorists are becoming increasingly radicalized. At the end of September, a 49-year-old man

shot dead a 20-year-old student and cashier at a petrol station after being told to wear a mask. Authorities said the murder was “no surprise” given the intensity of the COVID skeptic movement. Online, some Telegram users

glorified the murder and hoped more attacks would follow. “People are coming to us increasingly to ask, are my relatives dangerous?” says Tobias Meilicke, the head of another state-funded conspiracy theory counseling center, Veritas, founded in Berlin in January. (A third center in Germany is Sekten-Info, in the western state of Nordrhein-Westfalen, although conspiracy theories make up a smaller part of its work.)

Helping them and their family members maintain relationships and understand one another, Pohl says, is itself a way to prevent them from radicalizing.

Pohl says it’s important not to downplay the risk of terrorism, but also not to assume that everyone who believes in pandemic conspiracies and disinformation is an extremist in the making. “There are many people who are not violent at all and come from a completely different place,” Pohl says. “The large crowd does not go out and shoot around.”

Helping them and their family members maintain relationships and understand one another, Pohl says, is itself a way to prevent them from radicalizing. “If you feel understood, conflicts can be de-escalated and cease to be violent,” she says. On the other hand, “people who don’t feel understood get louder and louder.” Empathy is also important with an eye to the future: Conspiracy theories tend to lose their appeal as the crisis that created them ends. If believers still have contact with loved ones who are nonbelievers, that is often the easiest way out. If all contacts are broken off and conspiracy theorists are isolated, they’ll be more likely to radicalize further. Hence the centers’ emphasis on tolerance, acceptance, and de-escalation—Meilicke says their work is a way to “make people an offer to remain part of this society.”

But this theory—that the pandemic getting better will lead to de-escalation—isn’t actually playing out just yet. In the past few months, as the COVID-19 caseload decreased in Germany and widespread vaccination drove down the number of casualties, Pohl was sure she and her colleagues would have more time on their hands. But the opposite has been true: All three of the German counseling centers are currently overwhelmed. Pohl says her team can’t take on much more work; Sekten-Info is struggling to offer intensive follow-up appointments; Meilicke’s Veritas currently has a 60-people waiting list. “We have so many cases in Germany that we are no longer able to respond to them because centers like ours are few and small,” says Meilicke. They also report that cases are becoming more violent and radical.

Pohl thinks a point will come when pandemic-related fears and insecurity will abate, and when that happens, so will the polarization, conflicts, and conspiracy theories that prey on them. But she’s not confident she’ll stop being exposed to the grueling, kaleidoscopic spectrum of human misery—separations, fights, trauma, heartbreak, social media addiction—anytime soon. “In some cases, irreparable damage has occurred,” she says. Some people have developed enormous mistrust of the state; others have become radicalized past the point of no return. “I also think that new conspiracy theories will spread,” she said, causing her services to remain in high demand. “The question is whether they will change behaviors as much as they have in the pandemic."