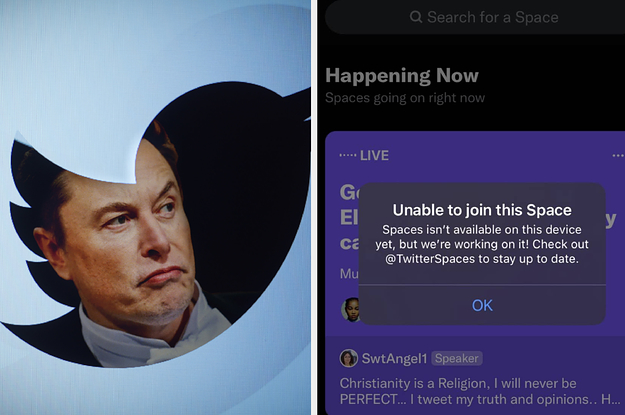

Twitter Spaces Were Taken Offline After Elon Musk Fled One Where He Was Asked About Reporters Being Banned

Musk fled a Space Thursday night after being grilled by reporters. Shortly after that, the Space was cut off, and the entire function was no longer available.www.buzzfeednews.com

Funny events in anti-woke world

- Thread starter Agema

- Start date

Again, sexual reproduction predates all extant animal species. Sex determination predates all extant animal species.None of this means that sex "didn't exist"-- just that humans had failed to recognise it or account for it in a very accurate way. Sex predates all extant animal species.

What I disagree with is that what humans call sex is synonymous with the above. Sex in the sense it's being used here is a system of classification based upon a flawed understanding of these mechanisms. There are medical texts written by human beings which go into extensive detail on the social conventions of how a doctor should determine sex in cases where it is unclear, because these are ultimately social conventions. They're guided by social priorities regarding what it is important for each sex to be able to do.

When I talked about the supreme importance of boys needing to be able to pee standing up, that wasn't a joke example. Actual doctors who probably take themselves quite seriously have argued that the ability to pee standing up is sufficiently important as to factor into the determination of someone's sex. If you think that's ridiculous, ask yourself the same question. What does a boy's body need to be able to do for him to "count" as a real boy? What quintessentially male experiences does a person need to be able to have in order to be a man?

It is sadly not.This is absolutely untrue, I'm afraid.

The reasoning behind men and women's different capabilities, prior to biological science, was that women were simply incomplete men.Pattern-recognition led us to those conclusions about the capabilities of male/female animals, and they seemed pretty reliable considering the pattern held in well over 90% of cases.

Men and women weren't actually thought to be very different, in fact it was commonly believed that women could physically become men through changes in their spiritual nature (I referenced an example of this earlier, it is not a particularly isolated one). This is why both men and women have semen. This is why the physical structures of the body have to be homologous. The body is the same, it's merely the presence or absence of "heat" or mystical energy that determines its expression.

But this understanding of pre-biological "sex" had far more implications than some irrelevant nonsense about genitalia. Women having weaker souls placed them lower on the hierarchy of being. It made them farther from God and closer to animals than men, less capable of thought, reason or moral conduct. These are the "capabilities" that were neatly transcribed into the language of sex, in the form of the innate inferiority of the female body and nervous system. For over a century, that belief in the intrinsic inferiority of women remained an integral part of the understanding of sex. In fact, it's closer to the original meaning of sex than any current ideas about sexual reproduction.

Right, but those beliefs were not bizarre or tangential. They were a huge part of the theoretical and practical understanding of sex. It's not some baggage that came along for the ride, it's an integral part of the concept that we've been painstakingly trying (and largely failing) to remove.Bizarre and tangential ethical/philosophical beliefs can be sparked by scientific discoveries.

Most people, I think, start by finding someone they actually like and are attracted to.Well, yes: because if someone wants to have a child, it will be incumbent on them to find someone they can interact with in a functional way so as to make that happen.

But sure. It seems entirely reasonable to talk about sexual reproduction in the context of people wanting to reproduce sexually. However, sexual reproduction is a thing that actually exists, which means it's completely different from arbitrary social identities assigned on the basis of the shape of people's genitalia many years before they can reproduce.

Again, I will stress that it is entirely possible to understand sexual reproduction without believing that the entire human race needs to be assigned into one of two arbitrary categories.A farmer wishes to sell eggs and milk. But his chickens won't lay eggs, and his cows won't produce milk. He tries to get a working population going through breeding, but they can't reproduce.

Sure, just like "race" is a descriptor that refers to racial characteristics (a fact which conveniently absolves us of any responsibility of questioning what those characteristics are or why they are important).Sex (distinct from gender) is a descriptor that refers to those sexual characteristics.

Sex does not have a neutral, universally accepted definition, but the most common definition is not descriptive at all, it's prescriptive. It's an attempt to define how human bodies and lives "should" function. Sex is not some distant planet that was discovered in a telescope one day, it is the product of a complicated history that predates the scientific method. It is shaped by social priorities that are deeply subjective and presume a shared understanding of what is and isn't important or desirable. There are rationalized definitions of sex that may have use in specific contexts. It may be relevant, for example, to refer to "gonadal sex" in a medical or scientific context, but this does not require the assumption of a sexed identity. The body can speak for itself.

It is possible to talk about bodies, about how they work and how they reproduce, without indulging the idea that those bodies fundamentally alter the nature and identity of the people who inhabit them.

Last edited:

Who? Musk? Exceedingly petty. A rich manchild accustomed to being god-king of his fief learning Twitter is not reality as his myth crumbles, and being unable to cope.How petty is this guy?!?!

Remember a little while ago, people saying they thought Musk buying Twitter would be a good thing, promote free speech and all?Who? Musk? Exceedingly petty. A rich manchild accustomed to being god-king of his fief learning Twitter is not reality as his myth crumbles, and being unable to cope.

Contact with people who know they're never going to benefit from his wealth is probably not good for his ego.Who? Musk? Exceedingly petty. A rich manchild accustomed to being god-king of his fief learning Twitter is not reality as his myth crumbles, and being unable to cope.

You know, I thought it was stupid when transphobes got up in arms over trans people in skateboarding and billiards, but disk golf? Fucking disk golf? Next you're gonna tell me there's a national mini golf authority that needs to make a decision about transgender people on the putt-putt course

First off: "disc golf". That person on Twitter was quoting the press release from the Professional Disc Golf Association, spelling it with a "k" is stupid.Never heard of disk golf, so I half-wonder if this is a PR stunt. There's lots of individuals on the net who get attention by picking stupid fights with others on the net, after all, maybe it applies to sports.

Second: it's not a PR stunt, and it isn't comparable to dividing mini golf by sex. The male professionals in the sport throw almost twice as far as the female professionals. I throw as far as most female professionals, and I'm exactly as athletic as you would likely assume me to be. In sanctioned events, the average male player beats the average female player by 10 strokes on an 18 hole course. In PDGA competition, players have ratings based on their performances. A pro-level male player is defined as having an overall rating over 1000. The best female player in the world right now is rated 988. I personally know men in my local area rated that high. It is, after all, a throwing competition. There are sports where protected divisions for women make more or less sense, this one makes a ton of sense. You wouldn't put men and women head to head on a discus competition, they don't even throw the same weight discus in competitions.

Third: there's already no such thing as the men's division in disc golf. There is MPO, mixed professional open, where anyone is allowed to join. FPO is female professional open, and is restricted to only (now biological) women. There's MP40, MP50, etc for Master's professional protected by age group, e.g. nobody under 40 in MP40. Then there are amateur divisions protected by rating: MA4 is novice (officially Mixed Amateur Division 4), MA3 is rec (under 900 rated), MA2 is intermediate (under 935), MA1 is advanced (under 970), and anyone rated higher than that has to play in the open divisions. There are similarly FA1-4 and FA40/50/60 divisions, for female amateur and masters players. Nobody is left homeless by this decision, there is already a system in place to have people compete against others of equivalent skills. The trans athletes are just going to be competing against people with male bodies and amateur skill sets instead of competing against people with female bodies and professional skill sets, because that is genuinely the difference body makes in the sport. Which they would already be doing regularly in casual events, as casual events don't have protected divisions most of the time, just general entry.

And for those who need an introduction to the sport, here's Philo's legendary albatross:

While I'm at it, the Jomboy breakdown of The Holy Shot:

It's 100% a real sport.

What you're doing here is pointing to flawed examples of how sex has been considered in the past, and implying that invalidates the entire concept. That's not rational or relevant.Again, sexual reproduction predates all extant animal species. Sex determination predates all extant animal species.

What I disagree with is that what humans call sex is synonymous with the above. Sex in the sense it's being used here is a system of classification based upon a flawed understanding of these mechanisms. There are medical texts written by human beings which go into extensive detail on the social conventions of how a doctor should determine sex in cases where it is unclear, because these are ultimately social conventions. They're guided by social priorities regarding what it is important for each sex to be able to do.

When I talked about the supreme importance of boys needing to be able to pee standing up, that wasn't a joke example. Actual doctors who probably take themselves quite seriously have argued that the ability to pee standing up is sufficiently important as to factor into the determination of someone's sex. If you think that's ridiculous, ask yourself the same question. What does a boy's body need to be able to do for him to "count" as a real boy? What quintessentially male experiences does a person need to be able to have in order to be a man?

"Sexual reproduction" and "Sex determination" you say yourself predates all extant animal species. Of course they're not synonymous-- those terms have additional context to them, referring to reproduction and determination. And yet both terms directly refer and relate to sex. They cannot exist without acknowledgement of different sexual characteristics.

The terms literally mean "reproduction related to sex" and "determination of sex".

Absolutely none of this is relevant. You could play the same game with any natural phenomenon-- write a long passage about how medical science doesn't exist because when researchers were outlining it hundreds of years ago they were referring to nonsense about the humours and miasma and devils.The reasoning behind men and women's different capabilities, prior to biological science, was that women were simply incomplete men.

Men and women weren't actually thought to be very different, in fact it was commonly believed that women could physically become men through changes in their spiritual nature (I referenced an example of this earlier, it is not a particularly isolated one). This is why both men and women have semen. This is why the physical structures of the body have to be homologous. The body is the same, it's merely the presence or absence of "heat" or mystical energy that determines its expression.

But this understanding of pre-biological "sex" had far more implications than some irrelevant nonsense about genitalia. Women having weaker souls placed them lower on the hierarchy of being. It made them farther from God and closer to animals than men, less capable of thought, reason or moral conduct. These are the "capabilities" that were neatly transcribed into the language of sex, in the form of the innate inferiority of the female body and nervous system. For over a century, that belief in the intrinsic inferiority of women remained an integral part of the understanding of sex. In fact, it's closer to the original meaning of sex than any current ideas about sexual reproduction.

No, they're not. None of these things are "integral", as demonstrated by the fact its extremely easy to acknowledge sex without buying into a single one of those extraneous belief structures without any contradiction whatsoever.Right, but those beliefs were not bizarre or tangential. They were a huge part of the theoretical and practical understanding of sex. It's not some baggage that came along for the ride, it's an integral part of the concept that we've been painstakingly trying (and largely failing) to remove.

We're not talking about "social identities". We're talking about a descriptive term that relates to that reproduction capacity. To be clear: not 100% coincidence. But relation.Most people, I think, start by finding someone they actually like and are attracted to.

But sure. It seems entirely reasonable to talk about sexual reproduction in the context of people wanting to reproduce sexually. However, sexual reproduction is a thing that actually exists, which means it's completely different from arbitrary social identities assigned on the basis of the shape of people's genitalia many years before they can reproduce.

Sexual reproduction literally means "reproduction related to sex". Remove sex, you remove the meaning of the term you yourself are employing in your own argument.

And it's also possible to acknowledge the existence of sex without believing the entire human race needs to be assigned those categories. You're conflating sex with all the surrounding societal baggage. It predates all that-- it predates our ability to even conceive of that baggage.Again, I will stress that it is entirely possible to understand sexual reproduction without believing that the entire human race needs to be assigned into one of two arbitrary categories.

I mean, in my example I'm not even talking about sex in humans, yet you've shifted it onto that. The farmer isn't acknowledging any "human categories" or blah-de-blah.

But by insisting that he also jettison the very idea of sex means he must consider every chicken as equally likely to be able to lay eggs, or equally likely to be able to mate with any other chicken. And that's patently absurd.

Indeed. But all this "nature and identity" guff is not required or necessary to acknowledge sex. There is zero contradiction in acknowledging sex without buying into those things. Hence why countless animal species, as well as plants and fungi, have sexes without any of that societal shite.Sure, just like "race" is a descriptor that refers to racial characteristics (a fact which conveniently absolves us of any responsibility of questioning what those characteristics are or why they are important).

Sex does not have a neutral, universally accepted definition, but the most common definition is not descriptive at all, it's prescriptive. It's an attempt to define how human bodies and lives "should" function. Sex is not some distant planet that was discovered in a telescope one day, it is the product of a complicated history that predates the scientific method. It is shaped by social priorities that are deeply subjective and presume a shared understanding of what is and isn't important or desirable. There are rationalized definitions of sex that may have use in specific contexts. It may be relevant, for example, to refer to "gonadal sex" in a medical or scientific context, but this does not require the assumption of a sexed identity. The body can speak for itself.

It is possible to talk about bodies, about how they work and how they reproduce, without indulging the idea that those bodies fundamentally alter the nature and identity of the people who inhabit them.

Ironically, you're conflating sex and gender.

They're either naive, lying themselves, or are just really dumb fucks that don't know what they want. Hope it was worth it you dumbasses.Remember a little while ago, people saying they thought Musk buying Twitter would be a good thing, promote free speech and all?

Last edited:

I was going to joke about tstorm learning the intricacies of an entire sport for his anti trans escapist crusade, but I actually think he might just be really into this disc golf thing, which totally tracks for a middle aged white dude.

I don't think anyone seriously thought that.Remember a little while ago, people saying they thought Musk buying Twitter would be a good thing, promote free speech and all?

I don't know, I've been thinking about that lately, when I was a teen in the early 10's I didn't have much that you could call firm political opinions, but I started to form some basic philosophical views, one of which was that utopian vision of the internet as something that would unite humanity by providing mostly free, mostly global communication and information.

And I lost most of those convictions as the decade went on. First as the user base of the internet became bottlenecked into a few large sites, and then as those sites became increasingly tighter controlled. That ideal of a universally available platform for communication and exchange of information turned out to be a pipe dream. And it was mostly not because of government bodies filtering information or gatekeeping access to it. The internet had been restricted and instrumentalized by the people who own it. Simple as that.

I think of that period from the early to mid 10's as kind of a honeypot to unite the growing userbase of the world wide web on a small number of sites with the promise of relative freedom and equality, before implementing all the algorithms that would eventually determine what content gets promoted and what content is fated for obscurity. So these sites turned from those public squares where common people could have conversations as equals to ones trying their damnedest to overwrite the informed opinions of individual to ones prefabricated and pre-approved by either the people providing the platform, or third parties that have invested a lot of money into a symbiotic relationship with them that lets them benefit off their automatized content filters.

There's just no substance to someone like Musk paying lip service to running a site he bought according to anything other than personal whim. He's in a position to make decisions unilaterally, so he will. As long as every piece of webspace that provides a public platform to its visitors is a piece of private property, the users will never have any real control over. Whether you can put a specific face to it, like you can with Musk for Twitter or Zuckerberg for Facebook, or it's people who place less value in self promotion, like whoever's making the decisions at Google, the internet's their world, we're just living in it.

And this is all a bit of a ramble, but my point is: If anyone is in a position to offer you freedom and decides just how much freedom you get and has the ability to take that freedom away whenever they want, it's not really freedom to begin with, is it? The consensus seems to be that there is now less freedom under Musk than there was under the previous management, which is probably true, I don't use Twitter, but as long as the users have no legally recognized ownership over a website, every bit of freedom they enjoy is basically on loan.

Election denier loses again.

Directly related^

-

Back to free speech free speeching all over the place...

Refresher on that;

www.businessinsider.com

www.businessinsider.com

www.thedailybeast.com

www.thedailybeast.com

-

Oh alright, one for the road...

Directly related^

-

Back to free speech free speeching all over the place...

Refresher on that;

Tesla knew its Model S battery had a design flaw that could lead to leaks and, ultimately, fires starting in 2012. It sold the car anyway.

In a rush to build the Model S, Tesla ignored the car's flawed battery cooling system design. And it's unclear when, if ever, the company fixed it.

Tesla knew its Model S cars were equipped with a battery-cooling system that had a flawed design in June 2012, as those cars started being delivered to customers, according to three people familiar with the matter and internal documents viewed by Business Insider. But the company sold the cars anyway.

The flaw in the design made the cooling system susceptible to leakage. Once coolant leaks into a battery pack, it can short a battery or cause a fire, industry experts told Business Insider.

This design flaw became a topic of urgent concern within the company in spring 2012, according to internal emails and documents viewed by Business Insider. And indeed, as cars were rolling off the production line and being delivered to customers in 2012, emails showed that Tesla employees were still concerned about the parts found leaking on the production line.

There were two main problems with the cooling system:

Tesla did not respond to Business Insider's detailed request for comment on these issues.

Both of these design flaws had the potential to cause leaks in the cooling system, meaning that the battery coolant could spill into a car's battery pack. Tesla continued to find leaking cooling parts — referred to as bandoliers or cooling coils — on its production line through the end of 2012, according to internal Tesla documents viewed by Business Insider. It is unclear when Tesla changed the design to prevent leakage.

The National Highway Transportation Agency is investigating whether Tesla Model S and Model X vehicles made between 2012 and 2019 had battery defects that could cause "non-crash fires." This came after a number of Tesla customers filed a petition complaining about a Tesla software update that limited the range their cars could drive on a single charge. Tesla made the update after a series of fires in 2019.

"Tesla is using over-the-air software updates to mask and cover-up a potentially widespread and dangerous issue with the batteries in their vehicles," consumer attorney Edward Chen alleged in a petition he filed to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration last year.

Tesla has been dealing with questions about the safety of its batteries for years. This is partly because the technology is new, and electric-vehicle fires are different from fires in traditional combustion engines. Because they're sparked by a chemical reaction, the fires can sometimes take days to put out, re-sparking hours after emergency responders have left a scene. It's almost impossible to find the source of a fire once the battery has been destroyed. The fires can also start spontaneously. In 2019, fires randomly started in parked Teslas in garages in San Francisco, Hong Kong, and Shanghai.

Jason Schug, a vice president at Ricardo Strategic Consulting who spent part of his engineering career at GM and Ford, told Business Insider he's done teardowns of Tesla's Model S and Model X vehicles, which share the same battery, as well as its Model 3. He told Business Insider that if coolant leaked into a battery module, it could render the battery useless.

"When we disassembled the Tesla Model X, a technician accidentally spilled coolant in the battery pack, and it sat there for a long time," Schug said. "There was no immediate danger, but when we removed the battery modules, quite a while later we found a lot of corrosion on the battery cells, and it was bad enough that some of the cells were leaking electrolyte. If this were to happen in the field and go unnoticed, it could result in bricking the battery."

"Bricking the battery" means that the battery would go dead.

Tesla did not respond to Business Insider's questions about its cooling system, batteries, or any possibility or impact of leaking fluid.

Schug also said that while the battery coolant itself is not flammable, the residue it leaves behind once it evaporates can be. This doesn't go for just Tesla but for all-electric vehicles. In 2017, BMW recalled 1 million vehicles for fire risk.

"There was an incident with another manufacturer that a vehicle that had been in a crash test spontaneously combusted weeks later," Schug said. "Coolant had spilled in the battery during the crash, and when it evaporated, it left a residue which conducted electricity into a short circuit, which overheated the battery and triggered a fire."

All of this is to say that an electric battery's design must do everything possible to ensure coolant doesn't leak into the battery pack — at least not without notice. If it does, consequences can be incendiary. Tesla did not respond to Business Insider's questions about how it prevents leakage.

Cars, but make it Silicon Valley

The promise of Tesla has been not only to make electric vehicles sexy but also to do so the Silicon Valley way — faster and cheaper than everyone else.

So when it came time for Tesla to design the battery for the Model S, it looked to use parts that already existed so it could keep things simple. It settled on the 18-650 battery cell — a cell that it could buy off the shelf because it was already being manufactured for everyday use in things like laptops.

To make a battery pack, thousands of these cells are grouped into over a dozen modules — the number depends on the battery's range.

But there is an issue with having so many cells in the battery: If a single cell overheats, it can set off a chemical reaction called "thermal runaway," in which other cells also then overheat and catch fire in an act of "sympathetic detonation." This is why — as with the case of the Tesla Model S that caught fire while it was parked in a garage in Shanghai in 2019 — it takes only one overheated cell or module to start the chain reaction that leads to a fire.

"There are really only a few reasons why a lithium-ion battery catches on fire," Brock Archer, an auto-extrication and fire-rescue expert, told Business Insider last year. Those reasons are "liquid, dead short," or, for every one battery cell in 1 billion, "spontaneous combustion," he said.

Tesla was keenly aware of these issues with electric-battery chemistry, explaining in detail the steps its design was taking to mitigate this risk in a battery patent filed in 2009. That is why — according to one former senior employee involved with the battery's design who spoke with Business Insider on the condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation — cell chemistry and battery structure were the company's main design concerns, cost aside.

The cell chemistry of the battery had to be precise to enable the car to reach long range and high speeds. And the car itself had to be designed to protect the battery at all costs in the event of a crash. This is because even a small amount of damage to a battery cell has the potential to set off this chain reaction, also known as "cellular propagation," when a temperature surge in one causes a chain reaction.

Because of the speed with which Tesla was going through the manufacturing process, it sometimes asked third-party suppliers to do research and development for the company, a former employee who left the company in 2018 said. Three former Tesla employees and two suppliers told Business Insider that this arrangement was not without friction. According to them, Tesla was sometimes dismissive of third-party suggestions, asked for more work than it paid for, and pushed suppliers to ramp up production volume at breakneck speed. These people, whose identities Business Insider verified, spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation.

As Tesla's need for battery modules grew, so did its need for cooling coils. In the initial Model S battery design, the aluminum cooling coils wound around the battery modules and connected to the car using end fittings.

"When you're launching a new component, there's always going to be difficulties and issues on line during first launch and especially when you're Tesla and you're asking your vendors to launch with a limited R&D," a former employee who left in 2014 said. "We did have problems with it leaking."

'Hanging by a thread'

By the time Tesla started workshopping issues with the Model S's cooling coils, the car's launch was already behind schedule. In his book "Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future," Ashlee Vance said that in an effort to get cars out of the factory as quickly as possible, Musk pulled employees from all parts of the business — from recruiting to the design studio — to sell as many cars as possible as fast as possible.

"If we don't deliver these cars we're f---ed," Musk said, according to Vance.

According to documents viewed by Business Insider, a few cooling coils were sent to a lab called IMR Test Labs in upstate New York in July 2012.

The results were not good.

According to the IMR report, which was reviewed by Business Insider, the end fittings on the cooling coils did not meet chemical requirements for a regulation-strength aluminum alloy. A source close to the matter said the results were shared with Tesla, but the Model S cars kept rolling out of the factory. According to Tesla's 2012 third-quarter earnings report, the company delivered more than 250 Model S sedans.

In August 2012, the part was tested again. Tesla sent the part to Exponent, an engineering and scientific consulting firm. According to internal emails reviewed by Business Insider, Tesla was concerned because the end fittings on the cooling coils were just not staying together and as such were a source of leakage. One Tesla employee described them as "hanging by a thread" in August 2012, according to internal emails viewed by Business Insider.

The engineer who handled this at Exponent was a man named Scott Lieberman. He is now at LPI Inc. Lieberman declined to speak with Business Insider about this story. In internal emails between him and Tesla viewed by Business Insider, however, his opinion of the part was clear. He found defects — specifically, tiny pinholes that caused the leaks — on the tested materials after limited testing.

Tesla continued to find leaking coils in various stages of production through the end of 2012, according to documents reviewed by Business Insider. Some were found late enough on the production line to be described as a "critical quality issue," or were found to have leaked liquid into the battery pack, according to internal emails sent in October 2012, which were viewed by Business Insider. At this point, the problem had been flagged for senior management, documents indicate.

In another email sent in September 2012, employees mentioned that workers on the production line sometimes had to use a hammer to get the end fittings to stay together.

Tesla did not respond to Business Insider's request for comment about these emails.

The employee who left Tesla in 2014 said these issues were considered normal by Tesla standards. Unlike traditional automakers, Tesla didn't wait for new models to redesign parts. Instead, parts were constantly redesigned and deployed into vehicles, the employee said. On the other hand, the former employee also said the company had "plenty of investigations and countermeasures" to try to reduce leaks.

Tesla did not respond to Business Insider's questions about its design process or the countermeasures it used to reduce leaks in this part.

The former employee who left the company in 2014 said the bends in the aluminum "made it more fragile" and that the end fittings were still sometimes forced together as they rushed to make production goals, causing leaks.

"We did find a few vehicles," the former employee said of cars that had leaks. "I don't know exactly how many, but again that is what I would consider normal for a company that decides to launch with a limited amount of R&D in the hopes of: 'We will launch with this, and we will put inspections in place that we catch it at the plant.'"

That, the former employees said, is just how things were done at Tesla.

It is not at all how a design flaw would be dealt with at a traditional automaker, like Toyota, according to Jeffrey Liker, a professor of industrial and operations engineering at the University of Michigan. He's the author of "The Toyota Way: 14 Management Principles from the World's Greatest Manufacturer."

Liker said automakers like Toyota front-load their manufacturing process. They put a lot of resources in preparation by creating and stress testing prototypes for new parts and then having a pilot production period to catch any flaws before the manufacturing process begins in earnest. Of course, 80% of the parts in most Toyota vehicles are from previous designs. Tesla, on the other hand, was designing an entirely new car — a process referred to in the manufacturing world as "clean-sheet design."

And when you start with a clean sheet, you have a lot more room for the innovation Tesla has brought to the table, but also a much higher risk of design flaws or production problems, Liker said.

"Every part of the vehicle was breakthrough innovation, so it was almost guaranteed there would be serious production problems," Liker said. "It's a trade-off, Musk could've been more conservative, but then what would be his competitive advantage?"

Tesla's processes

To try and understand how the company's production processes had changed since 2012, Business Insider reached out to three former Tesla employees who worked at the automaker at different times.

While none of them were able to confirm the extent of issues with the cooling coil, they all said Tesla was still an incredibly fast-paced place to work and that designs were in constant flux.

"Tesla is always driven by production, so sometimes if the issue isn't appearing for a customer, they'll just continue rolling out cars. It's as simple as that," an engineer who left the company in 2018 told Business Insider, referring to his general experience with the company.

Another employee who spent over a decade working for NUMMI (the Fremont, California, factory jointly owned by Toyota and General Motors that Tesla purchased) and four years working for Tesla told Business Insider that his experience at Tesla was very different from his time at NUMMI.

"Toyota did not rush through things like Tesla did," the employee who left in 2017 said. The same employee also said that though parts were tested rigorously, the workers testing them did not receive the same extensive training they would receive at NUMMI. There simply wasn't time, and Tesla's Silicon Valley engineers didn't want to hear much about how things were done at NUMMI, the former employee said.

"When I was hired they said they didn't want to hear about NUMMI or Toyota. 'We're a high-tech company, not an auto company,' they told me," the former employee said.

The former employee said the frequent changes in design created disruptions in Tesla's supply chain — upsetting suppliers — and wasted money and materials.

"Engineers would make a modification or change or something, and they would switch over to that," they said. "Then Tesla would have a truckload of products from the old style that they would waste ... that's how they run."

All three former employees said disruptions in the supply chain were wasteful for the company. One employee who worked at Tesla during the Model S launch said the joke inside Tesla was "that if you lined up the first maybe 10,000 Models S VINs, every single one would be different."

But this employee doesn't think any of that detracted from the work Tesla did.

"I think it's common in every auto company that vehicles are released with design flaws," the former employee said. "It's called running design changes."

Those design flaws, the former employee said, were what made room for Tesla's constant innovation at breakneck speed. Besides, the person said, Tesla's early adopters weren't really buying a car.

"It's my understanding that every customer back in 2012 was buying faith in Tesla. They weren't expecting a perfect car," the former employee said.

Musk Suspends Reporter Who Has Investigated Him for Years

Linette Lopez said she hadn’t tweeted details about the location of Musk’s private jet—his stated rationale for other suspensions.

It increasingly looks like self-described free speech absolutist Elon Musk is suspending Twitter users based on personal grudges instead of concrete principles. The latest victim: Insider columnist Linette Lopez, who has spent years aggressively covering Musk’s businesses, including documenting alleged safety lapses at Tesla.

In 2018, Musk disputed Lopez’s reporting, claiming that she had written “several false articles” and suggesting, with scant evidence‚ that she had bribed a former Tesla employee for information and was secretly “serving as an inside trading source for one of Tesla’s biggest short-sellers.”

“Have you ever heard anything more ridiculous,” she said on Friday of the allegations, laughing. “What a frickin’ fantasy.”

Lopez told The Daily Beast she received no explanation for her suspension, nor information about how long the ban will last. She said she hadn’t tweeted details about the location of Musk’s private jet—his stated rationale for other suspensions—but instead had been cataloging what she considered his hypocrisy over doxxing and targeting private citizens.

“I was just trying to highlight the fact that he talks about bullying and doxxing and all this stuff… And he’s a pro at it,” she said. “He harassed me back in 2018, he talked shit about me in the court of law, he sued my source. Like, I’ve been through the wringer with this guy. Nothing he does surprises me.”

Insider declined to comment; Musk did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Musk banned multiple prominent accounts over the past week, starting with the @Elonjet plane tracker. He then moved onto journalists who had covered the controversy, including New York Times reporter Ryan Mac, a former target of his ire.

In 2018, while working at BuzzFeed, Mac published emails from Musk in which the billionaire baselessly accused a British man working to rescue Thai children stuck in a cave of being a “child rapist.” Musk claimed the emails were off the record, but Mac never agreed to those terms.

On Thursday, after banning the reporters, Musk launched a Twitter poll asking his followers when the accounts should be reinstated. The listed options were “now,” “tomorrow,” “7 days from now,” and “longer.” Quickly, the “now” option took the lead.

Musk then launched a new poll.

“Sorry, too many options. Will redo,” he wrote. This time, he gave voters only two choices: “now” and “in 7 days.”

Once again, “now” sailed into the lead. As of early afternoon on Friday, however, the accounts were still banned.

Even some of Musk’s allies seemed to be questioning his tactics. Bari Weiss, one of the journalists Musk designated to distribute the “Twitter Files”—internal documents related to the platform’s historical approach to content moderation—suggested the billionaire had abandoned his absolute commitment to free speech.

“The old regime at Twitter governed by its own whims and biases and it sure looks like the new regime has the same problem. I oppose it in both cases,” she tweeted on Friday. “I have never been swayed by the ‘Twitter is a private company’ argument. And I’m left wondering… whether any unelected individual or clique should have this kind of power over the public conversation.”

Weiss took the opportunity to blast mainstream reporters who had expressed alarm about the recent bans, arguing that those journalists had not complained when right-wing users were suspended under the old leadership team.

Her comments seemed to agitate Musk. “What should the consequence of doxxing someone’s real-time, exact location be? Assume your child is at that location, as mine was,” he tweeted in reply, referring to the jet-tracking account he claimed led to a “crazy stalker” following his son.

When Weiss did not respond, he followed up. “Bari, this is a real question, not rhetorical. What is your opinion?” She did not immediately respond to that query either.

-

Oh alright, one for the road...

Last edited:

Those people were idiots, or liars.Remember a little while ago, people saying they thought Musk buying Twitter would be a good thing, promote free speech and all?

...whoops. Sorry, typo there. I mean those people were idiots, and liars.

You know those website that try to express large values that people don't really understand, like billions or the size of the sun or something, where you scroll for ages and ages and ages? Like that but with pettiness.How petty is this guy?!?!

"Ah hah! Little did they know, I was a frisbee-golf master!"I was going to joke about tstorm learning the intricacies of an entire sport for his anti trans escapist crusade, but I actually think he might just be really into this disc golf thing, which totally tracks for a middle aged white dude.

Disc golf is great, you should try it. I didn't even scratch the surface of intricacies, the physics is fascinating. Also 32 is not quite middle aged.I was going to joke about tstorm learning the intricacies of an entire sport for his anti trans escapist crusade, but I actually think he might just be really into this disc golf thing, which totally tracks for a middle aged white dude.

Gender is immutable unless you don't fit into certain gender norms. Too filled with hate to be capable of reason.

Living in everything-is-opposite-to-the-statement land must be a fucking nightmare. Imagine you go to pay for something and the person behind the till says it's 63p (assuming anything is still as little as 63p). Do you slyly ask them how much it is really?