Ugh, you could fill a whole thread about all the stupid shit that's been happening in Arizona for the past few years. Most surreal thing I've ever experienced is seeing that buffalo shaman in person during the summer 2020 protests and then seeing him all over the news later when Jan. 6th happened.

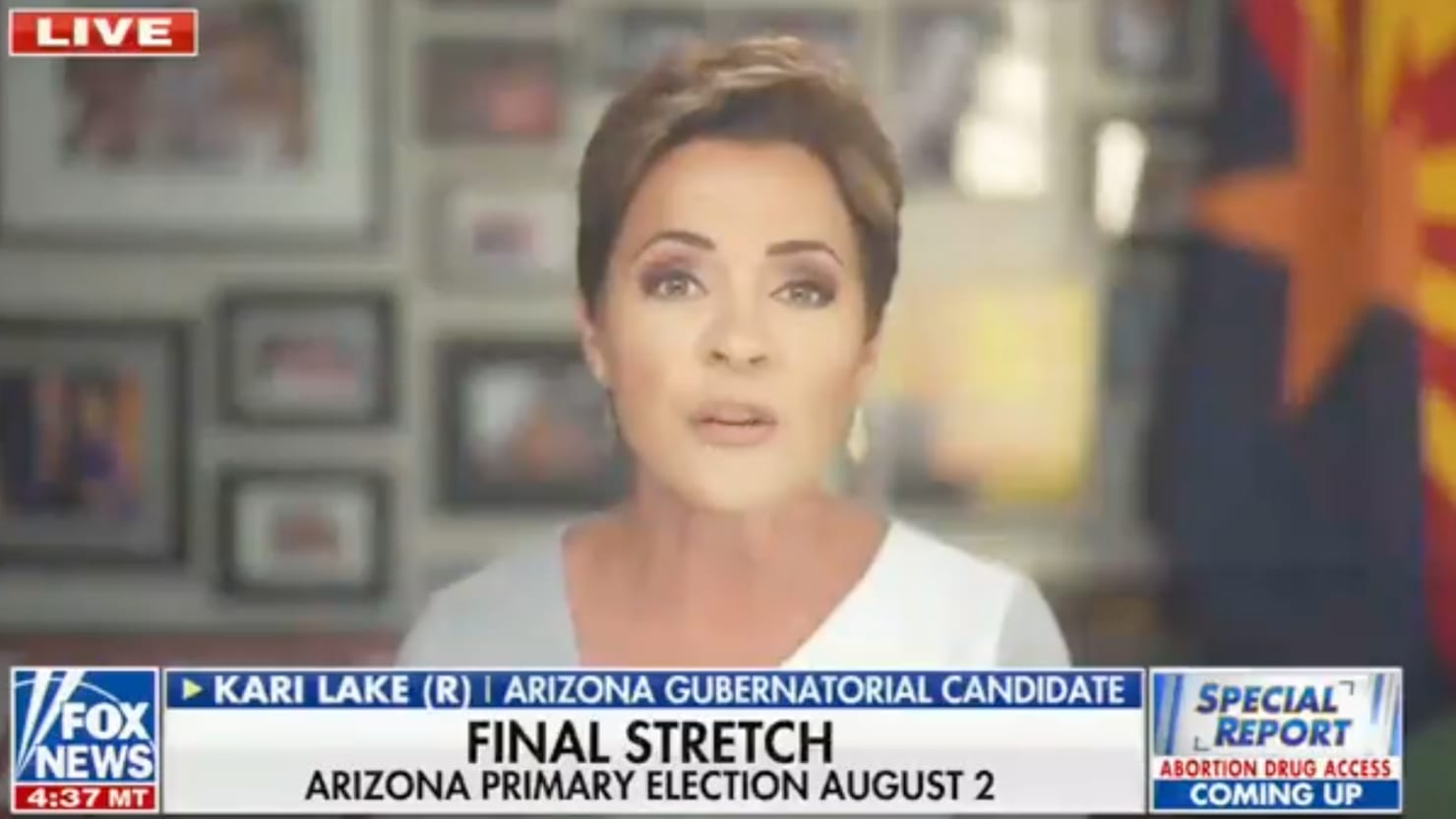

Lake is perhaps the most professional sounding of blatant grifters in the trumposphere, but it's not clear how much voting sway that'll earn her. Is no less concerning.

Further lake context;

Trump-Endorsed Candidate ‘Appalled’ When Fox News Host Mentions Drag Queen Story

“I thought you were a little better than CNN,” an upset Kari Lake complained to Bret Baier after he asked her about the story.www.thedailybeast.com

Funny events in anti-woke world

- Thread starter Agema

- Start date

The range had 4 lanes, each with their own target mount, all with the same target on top, which is what they saw as "all black men".I don't see any tape covering up any of the impact points on those targets. If you don't cover up the holes from a previous shooter before the next one fires, how do you know which shots were whose?

Now slavery is a naughty word

:watermark(cdn.texastribune.org/media/watermarks/2022.png,-0,30,0)/static.texastribune.org/media/files/bc9fd95e277ba07b7e49d0e45206bccf/Cactus%20Elementary%20MG%20TT%2004.jpg)

www.texastribune.org

www.texastribune.org

:watermark(cdn.texastribune.org/media/watermarks/2022.png,-0,30,0)/static.texastribune.org/media/files/bc9fd95e277ba07b7e49d0e45206bccf/Cactus%20Elementary%20MG%20TT%2004.jpg)

State education board members push back on proposal to use “involuntary relocation” to describe slavery

The Texas State Board of Education is fielding proposals to update the state’s public school social studies curriculum this summer.

That Spongebob bit is aging like fine wine with each passing day.Now slavery is a naughty word

:watermark(cdn.texastribune.org/media/watermarks/2022.png,-0,30,0)/static.texastribune.org/media/files/bc9fd95e277ba07b7e49d0e45206bccf/Cactus%20Elementary%20MG%20TT%2004.jpg)

State education board members push back on proposal to use “involuntary relocation” to describe slavery

The Texas State Board of Education is fielding proposals to update the state’s public school social studies curriculum this summer.www.texastribune.org

"Involuntary relocation" certainly has this greasily bland and anodyne feel of euphemism about it, like many others such as "collateral damage".Now slavery is a naughty word

* * *

Reminds me of this Texan I encountered who argued that Texas did not join the civil war to support slavery, but in protest about federal infringements on property rights. That was some brass neck, given the Texas declaration of secession states things like:

This document, morally dubious even by the standards of the time, should be seen as utterly shameful now. If modern Texas politicians now wish slavery to be taught as a perversion of the US Constitution, it demands deep soul-searching about the history of their state.[Texas] was received as a commonwealth holding, maintaining and protecting the institution known as negro slavery-- the servitude of the African to the white race within her limits-- a relation that had existed from the first settlement of her wilderness by the white race, and which her people intended should exist in all future time."

...

"these Southern States and their beneficent and patriarchal system of African slavery, proclaiming the debasing doctrine of equality of all men, irrespective of race or color-- a doctrine at war with nature, in opposition to the experience of mankind, and in violation of the plainest revelations of Divine Law."

It's got that faint smell of "extraordinary rendition" and "enhanced interrogation techniques", doesn't it? The ol' "let's not consider our victims to be actual human beings" feel.Now slavery is a naughty word

:watermark(cdn.texastribune.org/media/watermarks/2022.png,-0,30,0)/static.texastribune.org/media/files/bc9fd95e277ba07b7e49d0e45206bccf/Cactus%20Elementary%20MG%20TT%2004.jpg)

State education board members push back on proposal to use “involuntary relocation” to describe slavery

The Texas State Board of Education is fielding proposals to update the state’s public school social studies curriculum this summer.www.texastribune.org

This has absolutely nothing to do with my actual comment. Amazing!The range had 4 lanes, each with their own target mount, all with the same target on top, which is what they saw as "all black men".

It was the answer to your question. People were shooting in 4 separate lanes at identical targets, not shooting the same target in series.This has absolutely nothing to do with my actual comment. Amazing!

On a quiet Tuesday night in Howard County, Md., dozens of people gather in a community center and listen to Seth Keshel's 10-point plan.

"Captain K," as he's known in election fraud circles, is a former U.S. Army intelligence officer, and he is walking through his go-to presentation: comparisons of vote totals from the past few election cycles, which he falsely claims prove President Biden's win in 2020 was illegitimate. His 10-point plan to "true election integrity" includes banning all early voting and requiring all American voters to re-register.

The next night, more than a thousand miles away in Minneapolis, in a small building across from a popular garden shop, roughly 60 people wait for David Clements to take the stage.

Clements, professorial in a tan blazer with a graying beard and unruly curly hair, begins his presentation with a prayer. Then he goes to the slideshow.

The audience, which appears to be all white and mostly middle-aged, occasionally gasps as he shows charts and graphs, which he claims contain evidence of widespread election fraud.

Clements ends his talk with a request to the people in the audience: Go to the offices of your local officials.

"They respond to fear," he says. "You need to hold these institutions with the contempt they deserve."

An NPR investigation found that since Jan. 6, 2021, the election denial movement has moved from Donald Trump's tweets to hundreds of community events like these — in restaurants, car dealerships and churches — led by a core group of election conspiracy influencers like Keshel and Clements.

These local gatherings may reach fewer people than viral internet posts, but they seem to effectively spur action by regular people, who are motivated by their almost evangelical intimacy.

"It's this constellation of election conspiracy theorists," said Chris Krebs, a former Department of Homeland Security official who oversaw the federal government's election security efforts in 2020. "You can see the complexion of local politics shifting as a result. They have decentralized post-January 6th and are really trying to effect change at the lowest-possible level."

NPR monitored the election-denial influencers through events advertised on their public social media accounts, the websites and social media accounts of local organizations, events NPR attended, video footage and news reports over the past 18 months. Four prominent purveyors of voting misinformation stood out, crisscrossing the country to appear at at least 308 events in 45 states and the District of Columbia.

NPR tracked Keshel and Clements, as well as Douglas Frank, who misleadingly claims to have discovered a secret algorithm that swings vote totals across the U.S. (his methodology has been widely debunked by voting experts), and MyPillow CEO Mike Lindell.

The scale of their movements paints a portrait of an election denial movement that has evolved into a nationwide force, beyond just swing states — and despite the Jan. 6 Committee's investigation and efforts by voting officials at every level to combat disinformation. NPR's investigation is the first such effort to document the scope of these influencers.

"It's an existential threat to American democracy," said Franita Tolson, an elections expert at the University of Southern California. "If the numbers get big enough, it's unclear whether we will survive it."

The chain reaction

Carly Koppes, who runs elections in Weld County, Colo., says she noticed a tone shift in her county after Douglas Frank came to town.

She's reading over an email that just came in from one of her voters.

"Traitors will be exposed. These guys are going down and you have no chance..." She trails off as she scans. "You deserve everything coming your direction."

The Republican county clerk takes a long sigh.

Last summer, a group of suspicious citizens here knocked on thousands of doors looking to uncover evidence of election fraud.

"It started because of Dr. Frank and his really bad data analysis," Koppes said. "Him and his people, unfortunately, just don't know how to read election records correctly."

In his former life, Frank was a high school math and science teacher in Ohio. He's moved now into touring the country spreading election fraud conspiracies full time.

He, and the other three men whose movements NPR documented, either did not respond to requests for comment or declined to comment for this story.

In the visit Koppes mentioned, on April 24, 2021, Frank held court in a DoubleTree hotel conference room near Denver. Dozens of people cheered as Frank pointed at graphs that he claimed showed how the 2020 election was marred by fraud (something that's been debunked many times by hand counts, audits and investigative reports across the country).

"Go knock on some doors!" Frank implored.

And many people in this Colorado community listened.

A group popped up there, dedicated to this sort of fraud-motivated canvassing, and they devoted their organizing playbook to Frank.

Jim Gilchrist, a doctor of holistic medicine in Colorado, saw an online posting of Frank's talk and volunteered to canvass with the group. He estimates he spent more than 20 hours last summer knocking on doors.

"I just kind of wished there was some mechanism for there to be a more transparent kind of way of making sure the vote was counted correctly," Gilchrist said in an interview with NPR. "Douglas Frank kind of offered a solution that we could do as citizens."

Influencing policymakers

The election denialists also frequently bump elbows with people in power.

NPR found that over the past year and a half, the men met or appeared with at least 78 elected officials at the federal, state and local levels — many of whom will have a role in how future elections are run and certified.

At least two secretaries of state, two U.S. senators, 10 U.S. representatives, two state attorneys general and two lieutenant governors met or appeared with the figures NPR tracked. More than three dozen members of state legislatures, many of whom have introduced legislation in their states that would affect how Americans cast ballots, have also appeared at events with them.

"Our voices have gotten bigger and bigger every single day since last year and you cannot stop that," said Mike Lindell, at a rally in January of 2022 attended by three members of Arizona's congressional delegation, Debbie Lesko, Andy Biggs, and Paul Gosar, all of whom voted not to certify Arizona's election results at the U.S. Capitol a year earlier. "We will get our country back."

In some cases, the election denial influencers worked to persuade skeptical officials to embrace their claims.

In May 2021, Frank met with staff from the Ohio secretary of state's office for more than two hours.

NPR acquired audio of the meeting, which was first reported by The Washington Post, through a public records request.

The staffers in the meeting pushed back on Frank's many fraud accusations, and at one point he responded by threatening to send unauthorized people, or "plants" as he put it, into local voting offices.

"We have plants everywhere that go into buildings when your machines are on and capture your IP addresses. We have those, not necessarily in Ohio but we can arrange for that," Frank said, his voice rising. "So all I'm trying to point out to you is that this is coming. Be ready. And I'm not trying to fight you — do you see that I'm trying to help you?"

The staffers in that meeting didn't budge. But shortly after that meeting, someone did attempt to breach an elections network in Lake County, Ohio, though a state official told NPR that no sensitive data was ultimately accessed.

The four election denialists also appeared with well over 100 candidates for local, state and federal office in the 2022 primaries. Some, including U.S. Rep. Mary Miller of Illinois and state Sen. Doug Mastriano, who is running to be governor of Pennsylvania, have already won their party's nomination for the general election.

A fraud evolution

The highest profile of the group that NPR tracked is MyPillow CEO Lindell, a prominent and longtime Trump supporter.

Lindell says he has spent millions of dollars on his crusade, which started almost as soon as ballots were cast on Nov. 3, 2020. Sometime around March of 2021, he brought Frank into the fold and Frank's popularity skyrocketed.

"I went from being completely mum to suddenly 10 million people knowing me in about a week," he told a group in Utah last July.

Frank often speaks at events with Keshel and Clements. Clements is a lawyer and former professor at the New Mexico State University business school who was fired for not complying with the school's COVID-19 policies. Keshel is a retired Army captain and veteran of Afghanistan.

While those in the group often repeat talking points and appear together, they don't necessarily coordinate appearances or strategy. And other than Lindell, they were mostly unknown before 2020. Now they're influencers in the movement with online followings of hundreds of thousands of people. They even promote merchandise like T-shirts, books and body lotions, along with their election misinformation.

Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson, a Democrat, says they're using election fraud as a vehicle to advance themselves.

"There's no shortage of ability to access the truth about our election system, yet there seems to be a proliferation of people willing to lie about it," Benson said. "I think it's logical to conclude that they know better. And that they're knowingly spreading misinformation ... to win elections, to raise money, to gain attention and celebrity."

Benson says her office has seen a direct correlation between election denier events in Michigan and a rise in harassment toward voting officials.

"Whenever there is an appearance in which the former president or Lindell or others come out attacking our system we know to expect an uptick in threats and add additional security as a result," she said.

But she, and the thousands of other Americans in charge of elections nationwide, have yet to figure out a truly effective way to fight back and break through to the two-thirds of Republican voters who believe voter fraud helped Joe Biden win the 2020 election.

That's because election denialism has grown from a political movement into something almost religious, said Koppes, the Republican county clerk in Colorado.

"There's just so much that is incorrect that they just keep repeating and repeating and repeating," Koppes said. "And then as soon as I have absolutely blocked off that path with actual correct information, then they just move that goal post. And they keep just moving the goal posts. And moving the goal posts."

Between conversations with voters and research on all the separate false claims that have popped up over the past two years, she estimates she's spent thousands of hours dealing with the fallout of Donald Trump's misinformation campaign.

At this point, she says she's had to stop engaging with voters who are unwilling to listen to her.

"Some of these people really, truly believe they're doing the Lord's work," Koppes said. "But I think at the end of the day, they so desperately want to believe what they're being fed, that they're using all means to justify what they're doing."

This one is super long, cannot be arsed to attempt copy-pasting with this increasingly uncooperative phone right now;

Behind the Scenes, McKinsey Guided Companies at the Center of the Opioid Crisis (Published 2022)

The consulting firm offered clients “in-depth experience in narcotics,” from poppy fields to pills more powerful than Purdue’s OxyContin.

Last edited:

MSN

www.msn.com

Well, shit.

I mean, maybe it's not too bad, maybe the US can-

America Is Headed For Disaster

Donald Trump is on course to reconquer the White House. To save the republic, we need a radical change of direction.

Shit!

(Technically none of this is anti-woke per se, but it's Trump, so, meh.

I'm not sure how Trump announcing a campaign would be a distraction from Democrats campaigning.MSN

www.msn.com

It's not a distraction, it's the mere thought of Trump running, let alone being elected that's terrifying. And there's a strong chance that Trump would actually win.I'm not sure how Trump announcing a campaign would be a distraction from Democrats campaigning.

Chances are you disagree, but that's my view.

When Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp overwhelmingly won the Republican primary in Georgia on May 24, his chief opponent former Sen. David Perdue was quick to admit it was over.

"Everything I said about Brian Kemp was true, but here's the other thing I said was true: he is a much better choice than Stacey Abrams," he said shortly after polls closed, referring to the matchup this fall between Kemp and Democrat Abrams. "And so we are going to get behind our governor."

But another one of his opponents felt something was off.

"I want y'all to know that I do not concede," Kandiss Taylor said in a video posted to social media. "I do not. And if the people who did this and cheated are watching, I do not concede."

Kemp won Georgia's primary with about 74% of the vote. Perdue, who had the backing of former President Donald Trump, earned about 22% of the vote.

And Taylor? Just 3.4%.

Taylor is a fringe, far-right figure in Georgia with a history of making false claims about the 2020 election, voting machines and how elections are run. In the days following her defeat, Taylor has asked followers to sign affidavits stating they voted for her to prove she won the election — despite no evidence the vote totals are incorrect and with the deadline to challenge an election already passed.

Taylor is not an outlier, but rather an indicator of a new crop of candidates who insist they won their elections, facts be damned.

Election denialism is far-reaching in the midterm elections

While Trump has most notably spent the last 18 months denying his 2020 election defeat, despite clear evidence he lost, he's not the only one. During this election cycle, candidates across the country have refused to concede – even in races that are not remotely close.

This week, a Colorado county clerk indicted on charges including election tampering finished last in the GOP Secretary of State race, refused to acknowledge her loss and accused officials of cheating.

"We didn't lose. We just found more fraud," Mesa County clerk Tina Peters told supporters at an Election Night party."

In South Carolina, a pair of Republican primary challengers said their blowout losses were tainted by serious problems. Both gubernatorial candidate Harrison Musselwhite and attorney general candidate Lauren Martel lost by double digits against popular incumbents, but sent nearly-identical letters to state officials claiming a plethora of concerns with the election.

The South Carolina Republican Party's executive committee rejected the claims.

And in Nevada, GOP gubernatorial primary runner-up Joey Gilbert told supporters in a video message he could not have been defeated.

It's not based on any facts, it's only based on my gut feeling and my own intuition, and that's all I need."

Couy Griffin, a commissioner in Otero County, N.M. on why he wouldn't vote to certify an election

"It is impossible for me to concede under these circumstances," Gilbert said. "I owe it to my supporters. I owe it to all Nevadans of all parties to ensure that every legal vote is counted legitimately."

Gilbert, who was outside the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021 though he denies it was for the insurrection, has paid close to $200,000 for all 17 counties to recount the governor's race that saw him lose by about 11 percentage points. State and local officials reject Gilbert's claims.

In all of these cases, there is no evidence to back up claims of fraud that could reverse defeats, and most of these elections were not remotely close. But Matthew Weil with the Bipartisan Policy Center said, unfortunately, that doesn't matter to those who push the narrative of fraud.

"There is a very strong segment of the electorate that believes strongly if their candidate had lost, and they were doing well in the polls – even if they weren't doing well in the polls – it was the election machinery that caused their loss," he said.

The real world impact of false fraud claims

The vast majority of elections end uneventfully, even in close races, but a recent incident in New Mexico shows how election denialism is impacting local election procedures.

Commissioners in rural Otero County gained national attention for initially refusing to certify the results in the Republican-heavy area. After pressure and threat of legal action, only Couy Griffin voted no.

"My vote to just remain a no isn't based on any evidence," he said at a June 17 emergency meeting. "It's not based on any facts, it's only based on my gut feeling and my own intuition, and that's all I need."

Griffin called into the meeting from Washington, D.C., where he was sentenced for his role in the Jan. 6 Capitol insurrection.

It's not just fringe candidates making these claims, either. An NPR investigation tracked four election conspiracy influencers across hundreds of local events in 45 states and the District of Columbia, including meetings with at least 78 elected officials across all levels of government.

These sitting lawmakers can have power to shape legislation that alter voting laws and can make it harder for people to vote and easier to subvert results.

Weill, with the Bipartisan Policy Center, said you also don't have to look far to see why losing candidates could benefit from ignoring electoral reality.

"There are clearly now perverse incentives for losing candidates to keep up the fight long after the certification is complete and they've lost," he said. "And those incentives are that they can raise money for these challenges [that] often don't cost much because there's nothing to them, and they can use that money in future cycles."

The biggest example of fundraising off of a message of fraud might come from Trump himself. He raised more than $250 million to cover legal fees during his attempts to overturn the 2020 election for an election legal defense fund, according to the House committee investigating Jan. 6.

But that money, the committee said, didn't go to covering legal fees. Instead, it went to people and organizations aligned with Trump.

Voting experts and elections officials are worried this behavior will only increase in future elections, especially in battleground states where some elections aren't decided by such wide margins.

Last edited:

They don't actually care about the votes because they don't care about democracy. They just want power.