Steve Bannon ordered to prison while he challenges his conviction for defying Jan. 6 committee

U.S. District Judge Carl Nichols, a Trump appointee, had previously paused Bannon’s four-month sentence while he appealed his conviction.

Steve Bannon: No prison or jail 'will ever shut me up'

Steve Bannon: No prison or jail 'will ever shut me up'

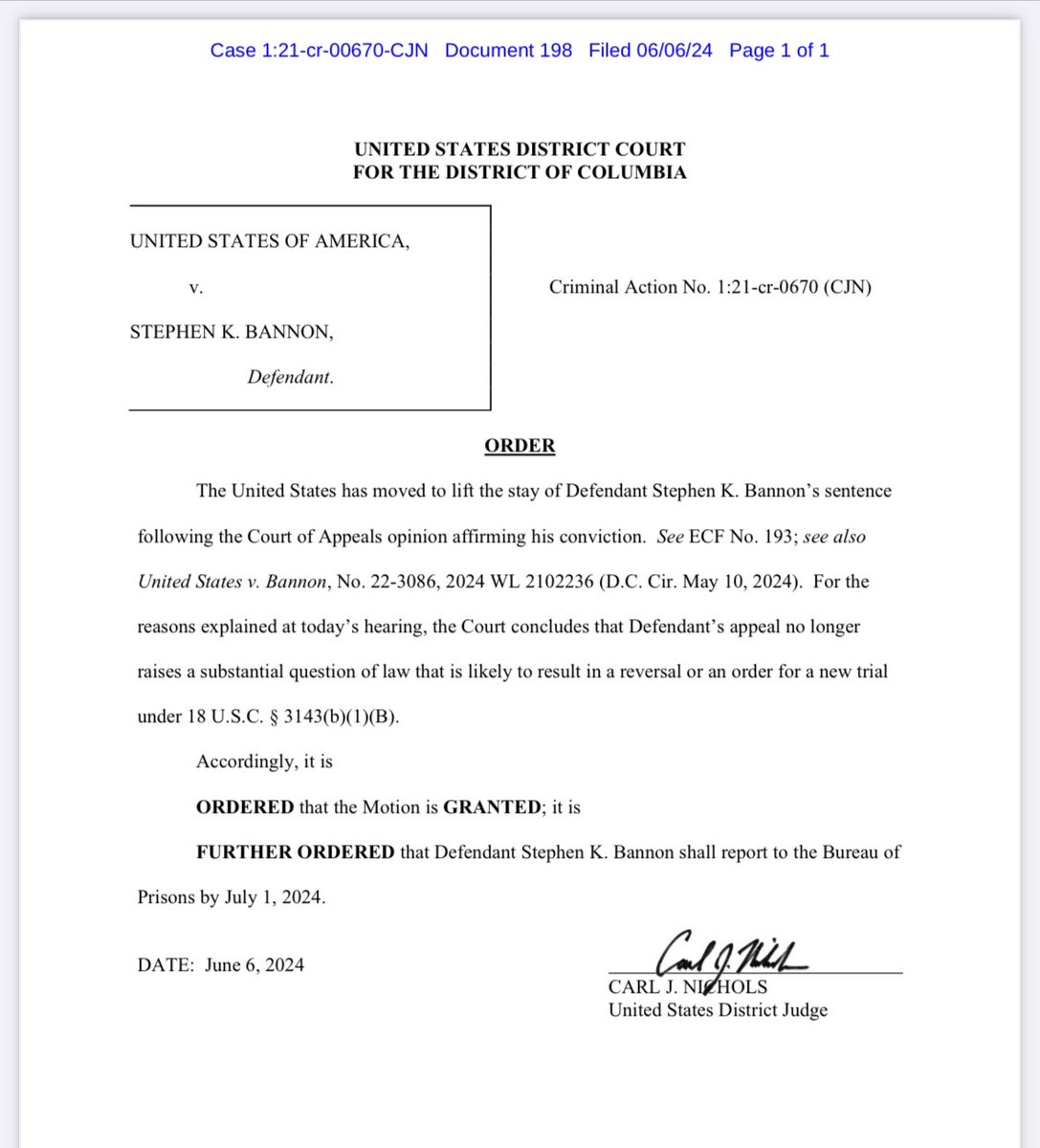

A federal judge has ordered Steve Bannon, a longtime ally of former President Donald Trump, to report to prison by July 1 for his conviction for defying a subpoena from the Jan. 6 committee.

U.S. District Judge Carl Nichols, a Trump appointee, previously paused Bannon’s four-month sentence while he appealed his conviction. But on Thursday, Nichols ruled that the original reasons for the postponement no longer apply because a D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals panel

ruled strongly and unanimously last month against Bannon’s position.

Bannon intends to continue appealing the case to the full bench of the D.C. Circuit and the Supreme Court. But unless one of those courts steps in to block Nichols’ decision, Bannon is unlikely to be able to stave off prison in the meantime.

If Bannon indeed heads to prison on July 1, it would put him behind bars until just before the November election. In addition to keeping Bannon — who hosts a popular far-right podcast — off the air for a crucial stretch of the election cycle, Nichols’ decision would also effectively pardon-proof Bannon’s jail sentence. (Trump

pardoned Bannon on the final day of his presidency on federal fraud charges.)

Bannon was convicted in July 2022 of two misdemeanor counts of contempt of Congress for stonewalling a subpoena from the House select committee investigating the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol.

“I do not believe that the original basis for my stay of Mr. Bannon’s sentence exists anymore,” Nichols said from the bench of the federal district courthouse in Washington, D.C.

Bannon was flanked by his lawyers David Schoen — who once represented Trump in his impeachment proceedings after Jan. 6 — and Evan Corcoran, who is a key witness in the criminal case against Trump in Florida, where Trump is accused of hoarding classified documents after he left the White House.

Bannon is the second former Trump White House adviser headed to prison for defying the Jan. 6 committee. Peter Navarro, a former Trump trade adviser, is currently serving a four-month sentence in Miami for blowing off a subpoena from the panel. The appeals court’s rejection of Navarro’s bid to stay out of jail was a key factor in Nichols’ decision to revoke Bannon’s bail.

The Jan. 6 committee subpoenaed Bannon early in its investigation as part of an initial wave of outreach to key Trump advisers involved in his efforts to subvert the 2020 election. The panel cited reports that Bannon and Navarro worked together on what they called the “Green Bay Sweep” strategy to orchestrate challenges to the election results in Congress on Jan. 6. Bannon also warned on his popular “War Room” podcast the day before Jan. 6 that “all hell is going to break loose tomorrow.” And White House call logs obtained by the Jan. 6 committee showed Trump and Bannon were in touch at key moments in the run-up to Jan. 6.

Nichols also said his decision to revoke Bannon’s bond was based on the appeals court’s full-throated ruling in Bannon’s own case, which sharply rejected the key issues that Nichols once said might cause the appeals court to revisit the conviction.

“We’re going to go all the way to the Supreme Court if we have to,” Bannon said after Nichols’ decision. “There’s not a prison built or jail built that will shut me up.”

Schoen called on Speaker Mike Johnson to formally declare the Jan. 6 committee’s previous subpoenas invalid, contending this would add legal weight to Bannon’s appeal.

It’s unclear how receptive the appeals court or the Supreme Court will be to a plea from Bannon to remain free. Earlier this year, Navarro struck out at the appeals court and made a similar pitch to Chief Justice John Roberts, who oversees emergency matters arising in Washington, D.C.

Roberts

turned down Navarro’s request without even referring it to his fellow justices, even though such a referral is the common practice in controversial or legally substantive matters. The chief justice did write

a brief, solo opinion explaining his ruling, appearing to agree that Navarro’s lawyers “forfeited” certain arguments by not raising them at earlier stages of the litigation.

Having observed Navarro’s legal saga, Bannon’s attorneys may have a chance to avoid some of those pitfalls.

Navarro reported to a federal prison in Miami the day after Roberts’ ruling. He remains there serving his four-month sentence.

Nichols emphasized that the issues in Navarro’s case were distinct from Bannon’s because Navarro was working in the White House on Jan. 6 while Bannon had departed the administration years earlier.

Navarro’s case turned on whether Trump had invoked executive privilege to bar Navarro from speaking to the Jan. 6 committee, a claim that the judge in his case rejected.

Bannon, on the other hand, said his decision to refuse the Jan. 6 committee’s subpoena was based on the advice of his lawyer — at the time, Robert Costello — who said Bannon was immune from the panel’s demands.

However, Nichols rejected that claim,

citing the 1950s case of mobster Peter “Horseface” Licavoli, who was held in contempt of Congress despite a lawyer’s advice that he decline to appear for testimony on organized crime. The D.C. Circuit held that witnesses who “willfully” refuse to comply with valid congressional subpoenas can be punished, regardless of the excuse.

Nichols signaled during Bannon’s trial proceedings that he disagreed with the decadesold decision but said he was bound by it because district court judges are required to apply the decisions of the appellate courts. His decision to initially postpone Bannon’s sentence was rooted in part on his belief that the appeals court might signal a desire to reverse the Licavoli ruling. But when the panel sharply rejected that argument, Nichols said his view that the decision might be reversed no longer applied.

www.vox.com

www.vox.com